PERIOD I. 1811-1831

IN the autumn of the year 1811 a number of private gentlemen met in Dublin, and founded the Society for the Education of the Poor of Ireland, which soon became known generally as the Kildare Place Society.

All through the eighteenth century the only education planned by England for Ireland was one which aimed at alienating the Irish from their religion. Proselytism was the natural complement of the Penal Laws. It remained for these Dublin gentlemen to discover and inaugurate a new policy. The modern expert would describe as 'undenominationalism' the system they invented. In the absence from contemporary language of the specific word, these pioneers gave expression to their aims by saying that the leading principle which governed them was a desire 'to afford the same advantages for education to all classes of professing Christians without interfering with the peculiar religious opinions of any.' So far back as 1786 this plan had been formulated in connexion with a large Dublin School; it sprang into national prominence when the limited and local school committee developed, in 1811, into The Society for the Education of the Poor of Ireland.

Accustomed as we are to-day to the postulate that every child must be educated, we commonly forget how extremely modern this universal education is. Yet not many years have passed since instruction was considered the poor man's bane, instead of his blessing, since duty for many seemed to consist in barricading, rather than in opening up the paths of learning. When George III. expressed a wish that every poor child should be taught to read the Bible, a medal was struck forthwith to commemorate a sentiment at once so revolutionary and so uncommon.

It is necessary to recall these facts if any adequate estimate is to be formed of the calibre of the new Society. Had these Dublin enthusiasts accomplished nothing they would deserve honourable commemoration for the boldness and comprehensiveness of their initial programme -- education for all without interference with the religion of any.

When once the novelty of the aspirations of the Society has been grasped it will be less difficult to picture the magnitude of their task. The extent of this task may be expressed in condensed form by a single word-everything. If we except the genuine desire for learning which has always been characteristic of the Irish, there was nothing upon which the Society could count as an asset. In its ultimate analysis the work of education implies-teachers to teach, buildings in which to teach, and apparatus to supply the means of teaching. If the work is to be permanent, it further demands skilled supervision to encourage excellence, and detect failure. To-day each of these divisions is entrusted to a separate. organisation. We look to the Training Colleges for our teachers, to the localities for the buildings, to the publisher and furniture manufacturer for apparatus, and to the Government for supervision.

For all these requirements the Society for the Education of the Poor of Ireland looked solely to themselves; and, furthermore, they expected from their own resources, and the interest they hoped to arouse everywhere, to provide all the funds required for their colossal enterprise.

Not less remarkable than their courage was their foresight. They made no plunge haphazard into a work whose complexity only became apparent as it proceeded. From the outset they had clear vision of the duties which lay before them, and they made ready for their full discharge.

The first report is busy with plans for the training of teachers. Unwilling to wait until in possession of a Training Institution of their own, they made temporary arrangements with the large school already mentioned, engaged a training master at a salary which was nearly half their available income, and began to train teachers just two years and two months from the date of their foundation.

Equally prompt were their plans for providing suitable school buildings. So soon as funds permitted, grants towards the building and equipping of schools became a regular part of the system ; but here also so much as was possible was undertaken at once. If they could not build schools themselves, they could, at least, teach others how to build them. Even before the commencement of training they prepared and put into circulation a twenty-four page 'Tract' upon the subject. 'The little book is a model of clear arrangement and good print. Directions are given as to sites, roofs, floors, plans, windows, doors, and fires. Careful measurements are supplied. The whole is illustrated by three excellent plates. Two are ground plans of schoolrooms of different sizes. The third consists of working drawings of desks, adapted for being fixed either on boarded or in clay floors.' (Quoted from the writer's 'An Unwritten Chapter in the History of Education.' Macmillan & Co., 1904, where a full account is given of the Publications of the Society.)

It was the same with the required apparatus. In 1811 there were no school books in the modern sense. The custom of the day, wherever children were instructed, was for each to bring what book he chose, and to stumble into the reading of it as best he could. The Society immediately set to work to supply the deficiency. In 1813 they published a 'Spelling Book' and a 'Reading Book.' These were followed by works on Arithmetic, Needlework, Geography, Geometry, Trigonometry, and Mechanics. They also issued a 'Schoolmaster's Manual,' which gave a full and clear account of the system of school management practised in their training school, and they compiled a series of ' Cheap Books' for the purpose of supplying their schools with Libraries.

The fourth of the specified requirements -- supervision -- from the nature of the case came later; but so soon as teachers and schools were ready, inspectors were set to work, and the closest watch was kept on the progress made and the results obtained.

With such evidence before us of courage and foresight, it will cause no surprise to be told that the work thus planned was soon crowned with remarkable and signal success. The early history of the Society reads like the narrative of a triumphant progress. Their liberal policy met with welcome everywhere; men of all religions united in working with or for them. They tell us in their Second Report that 'the improvements lately introduced into the systems for the education of the poor have become the subject of discussion among the enlightened, and even the theme of conversation among the fashionable, and wherever mentioned every tongue seems eager to expatiate upon the happy consequences which must result.' What men thought of the work is shown by the readiness with which the leaders both in politics and society identified themselves with the Committee. The Duke of Kent became Patron, The Duchess of Dorset and the Duke of Leinster, VicePatrons; a number of the most prominent of the nobility accepted office as Vice-Presidents; Daniel O'Connell, and many others equally well known, enrolled themselves as members. Nor was it long before the Government began to take a practical part in the chorus of approval. Mr. Peel, afterwards Sir Robert, was Chief Secretary. He believed in education, and he believed in the Society's plans for educating the Irish. He himself early became a subscriber to their funds, and he was not long in coming to the conclusion that the Society formed a fitting channel for the expenditure of any funds Parliament might be induced to vote.

Much as the Committee appreciated the confidence of such a man as Peel, they viewed with mixed feelings the prospect of State subsidies. Instinctively they foresaw the dangers involved -- on the one hand, restricted freedom; on the other, accentuated jealousy and unrestricted criticism. Had they been free to choose they would have respectfully declined the tempting offer. But the funds placed at their disposal from voluntary sources, though liberal, considering the time, were so far out of proportion to the magnitude of the work that there was really no course open but to accept Parliamentary assistance, if their plans were to be carried into operation.

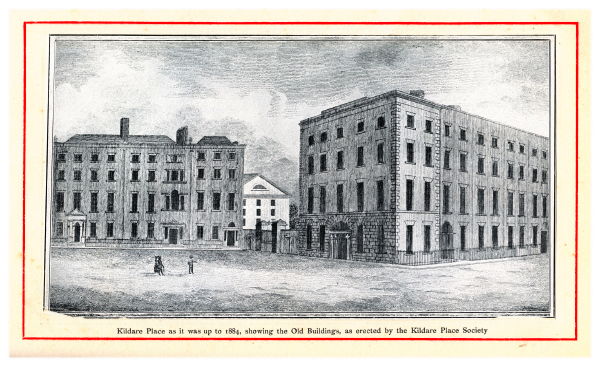

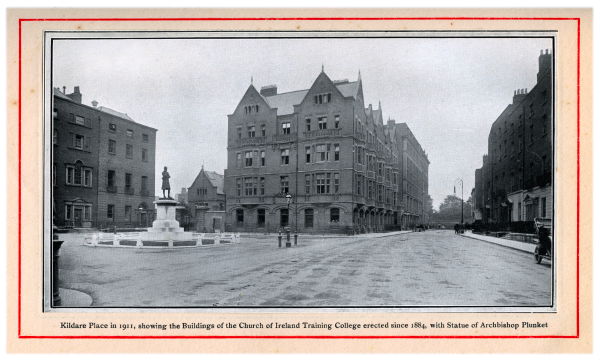

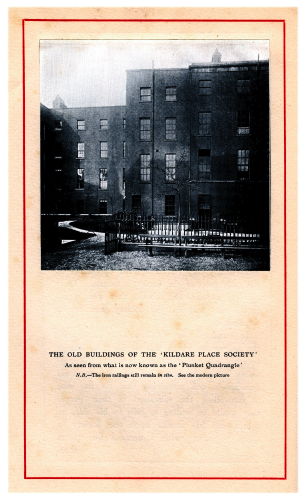

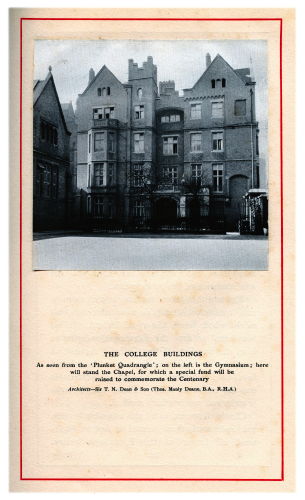

All serious difficulties with reference to finance having thus been laid to rest, rapid progress was made in every direction. A central and important site was procured, from which came the short title commonly used henceforth-the 'Kildare Place Society.' Great schools were built which embodied all that was best in the educational architecture of the period. Accommodation was arranged, first for masters, and then for mistresses, to come from all parts of Ireland to be trained. A large Depository was opened for distributing school requisites, either in the shape of free grants, or at lowest prices. Soon applications for help in founding and maintaining schools came pouring in from all quarters. To meet them, a careful system was devised for stimulating local activity by central help. Wherever a willingness to co-operate and to contribute was shown, grants were made, first, towards the building and equipping of the schools, afterwards in aid of the teachers' salaries. Finally, all Ireland was mapped out into eight inspection districts. Such was the interest and enthusiasm evoked that men of high social standing and marked ability accepted service as inspectors at extremely moderate salaries. Not alone did they carry through the work of inspection proper with a care and exactitude which has not since been surpassed, but they also planned schools, superintended buildings, and, in general, acted everywhere as convinced and active propagandists of the Kildare Place ideals and system.

What the Society, thus organised and thus assisted, succeeded in accomplishing may be summarised as follows:-- From the Training School went out each year some 150 masters and some 60 mistresses; the total from 1814 to 1831 was nearly 2,500. Each year about 60,000 copies of the 'Cheap Books' were sold; by 1833 the output amounted to upwards of 1,500,000. From the first, Libraries 'were attached to every School. In 1822 separate 'Lending Libraries' were begun; they numbered 1,100 by 183 I. The Schools founded or assisted by the Society increased steadily until they covered the whole of Ireland. In 1816 there were eight; in 1831 they had spread into every county and had risen to 1,621. Pupils to the number of 137,639 were in attendance; the average per school was between 84 and 85.

In the face of such a list of achievements it will be no surprise to hear that the Society, which, in less than twenty years, could accomplish so much, had attained to a European reputation. The fame of the Kildare Place Schools procured them the honour of a visit from the' man who was probably the chief educational expert of the time. The Count de Lasteyrie travelled from France to see for himself the Model School in Dublin, and he felt his time and labour so well repaid that he pronounced the School to be the best in existence, and said it should serve as a Model, not only for Ireland, but for every country in Europe.

From Scotland numbers of distinguished visitors crossed and inspected the Schools in the Counties of Antrim and Down. Professor Pillans, Professor of Humanity in the University of Glasgow, and well known at the time as a writer and lecturer upon education, devoted a season to a detailed study of the Kildare Place system, with the result that he felt compelled to admit, reluctantly, that the Irish schools were a hundred years ahead of those in Scotland. Very generous also was the tribute paid by the British and Foreign Society. In their Report for 1822 they say 'it must be peculiarly gratifying to every friend of his country to learn the rapid strides which education continues to make in that island. . . This Society has spread blessings over Ireland'; and in the Report for 1824 'the Committee turn to Ireland with feelings of grateful exultation. The Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor is advancing with gigantic strides. Supported by the munificence of Parliament, and managed with great zeal and prudence, this Society becomes every year more interesting and important. The success of the past year is most exhilarating.'

It will presently be our duty to glance at the causes which brought to a close this brief but brilliant career, but first a word must be spoken as to the spirit of the men who planned and guided the Society. Space will not permit the mention of more than a name or two; this, however, is the less to be regretted because the conspicuous feature was the way in which the Committee and its Sub-Committees worked together as a whole. Not self, but the cause, was their guiding principle. Especially prominent were Samuel Bewley, a Quaker, and Joseph Devonsher Jackson, afterwards Judge of the Common Pleas; but there were many others who gave ungrudgingly of their time and talents. As they were for the most part either busy merchants or professional men, the beginning was the only portion of the day available. Accordingly, 8 a.m. was the hour of meeting. A hurried breakfast, and a long session took place once a week for the General Committee. The permanent Sub-Committees, of which there were six, were also expected to meet weekly. At periods of pressure they had often to adjourn from day to day; daily meetings of one or more Committees were not uncommon at Kildare Place.

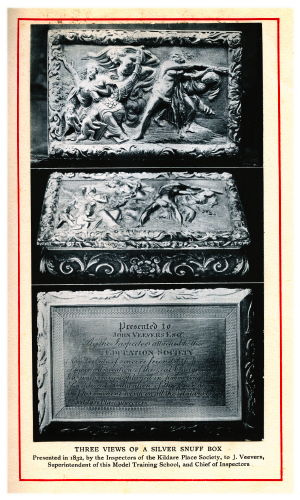

The secret of the remarkable success which attended these zealous workers, seems to have lain in their readiness to absorb everything that was good in the systems of the time, together with their capacity for original development. As we have seen, some of them had had considerable experience in school management before the foundation of the Society. In the large Dublin school, with which they had been connected, many of the improvements usually associated with Dr. Bell or Joseph Lancaster took independent origin. It was so with the principle of class teaching, and the monitorial system. This, however, did not prevent their inviting Lancaster, who was on tour in Ireland at the time, to be present at their early meetings of Committee, and they made him a handsome payment for the right to publish his books. Similarly, when an official head became necessary they appointed a master, John Veevers, whom Lancaster had trained. When he came, they explained that he was at liberty to graft upon the Irish system any of the Lancasterian methods which promised to be profitable, and they encouraged him to press forward on his own account, upon new and original lines. John Veevers responded enthusiastically to this treatment. He proved himself a genius in the work of educational organisation, and as such he deserves an honourable place among the pioneers of Elementary Education.

In the Rev. Charles Bardin, who had charge of the literature, the Society were equally fortunate. Ready always to sink his own personality, he made full use, upon honourable terms, of all books that seemed suitable. He was, however, no mere compiler; the long series of interesting and instructive works, which he wrote or arranged, show him to be an author and editor both versatile and original.

With reference to the work of the Committee themselves it only remains to be added that, notwithstanding the vastness of the labours which they undertook, and the largeness of the grants with which they were entrusted, their services were rendered gratuitously; even the expenses of their breakfasts were all privately defrayed.

Their spirit shows itself finely in the reply which was given to the astonished Royal Commissioners who investigated the working of the Society in 1825. 'Do you receive any remuneration?' they asked Mr. Jackson. 'Not pecuniary,' was his answer. 'I apprehend we shall receive ample remuneration hereafter from witnessing the improved state of the country.'

It is now time to ask how it happened that, notwithstanding all this educational efficiency, the Government Grants were withdrawn in 183 1, and the duties of the Kildare Place Society transferred to the National Board.

The explanation lies ready to our hand-it was the Simple Bible Teaching that made the continuance of the grants a political impossibility. At first sight it seems strange that a principle which had always been of the essence of the Society'S policy should admit of success for a time, and yet in the end ensure destruction. N or have there been wanting those who accused the Committee of departing from the broadminded toleration which had been their most attractive characteristic. For such a charge as this, no foundation exists. Alterations there undoubtedly were; they took place, however, not in the Society, but in their environment. Truth to tell, at no time was any warmth of welcome shown for the fundamental rule which insisted that in every school the Scriptures must be read 'without note or comment.' It was in spite of, not because of, this requirement that Kildare Place flourished. The Established Church was never enthusiastic in its support. Its members objected to the prohibition of doctrine. The Roman Catholics patronised only because no other means of education seemed within their reach. They had the strongest objection to compulsory Bible reading, and whenever it was possible they avoided compliance with the rule; but they recognised that the Committee meant to deal fairly by them, and they gave them credit for discountenancing the proselytism which had previously prevailed. Accordingly they refrained from opposition in the early years of the Society'S success. Their children attended the schools, they were represented not only in the Society, but on its Committee.

It remained for O'Connell to inaugurate the movement which was destined to change accepted alliance into open hostility. Recognising what the power of the ,Priests could accomplish, and perceiving that for the sake of controlling the education of their people they I would be willing to rally to his side, he commenced his attacks upon the Society in 18 19, beginning with a demand for reform from within. As we have seen, O'Connell and many other Roman Catholics were members. They attended the Annual Meeting of the Society, and proposed a resolution calling for a radical change in the constitution. The speech of O'Connell is extant. The Society took pains to have it preserved. It denounces with bitterness the rule which insisted on the reading of Holy Scripture, and in the name of the Roman Catholics proclaimed war, unless the rule was abolished. When a majority of those present declined to entertain the proposed alterations, O'Connell and his supporters withdrew, and founded straightway an opposition Society, with the avowed object of ruining Kildare Place, and obtaining for themselves the administration of the public grants.

The step thus taken was fraught with momentous consequences, not alone to education, but to the whole future history of Ireland. It has been usual to date the Emancipation agitation from the founding of the Catholic Association in 1823. In reality the foundation date should be 18 19. What made the agitation practicable was the attack on Kildare Place, and the sense of unity and power which resulted.

Clearly, however, as all this can now be seen and understood, there seemed at first no likelihood of danger to the Education Society.

Wholly undeterred they pressed forward actively, adding continually to the scope and efficiency of their work. It was not till 1824 that the first real blow fell. In response to the increasing clamour of the Society's foes, a Royal Commission was then appointed to investigate their operations. In all respects, save one, the report of the Commissioners was a splendid vindication, both of the integrity, and the success of the Society. The solitary exception was the defect upon which O'Connell had fastened. In the opinion of the Commissioners the reading of the Bible without note or comment was universally disliked, and enough in itself to vitiate the Kildare Place system. After the publication of an opinion, at once so clear and so authoritative, it was plain that if the Society meant to retain their grants they must alter their fundamental rules. This they declined to do. Faithful to the principles on which they had been founded, the Committee determined to continue their resistance to the end. Their courage and fidelity did not go unrewarded. Powerful friends such as Peel, now Home Secretary, continued to advocate their support. Their own zeal and skill ensured them an increasing measure of educational success. But the more efficient the Education Society showed themselves to be, the fiercer grew the attacks upon them. When Wellington and Peel unwillingly yielded to the demand for Emancipation in 1829, it was manifest that there were forces at work which could not long be kept at bay. Wellington's retirement in the following year was the signal for the . final blow. The end came at the hands of Earl Grey and Mr. Stanley. Not because they altered, but because they refused to alter their principles, the Kildare Place Society went down.