THE CASTLE FIRE.

On the accession of Queen Anne, 1702, the Borough of Belfast consisted of four continuous thoroughfares under eight different names -- High Street and Castle Street; School House Lane and Skipper Street; Bridge Street and North Street; Broad Street alias Waring Street and Rosemary Lane. The Corporation Church alias The Chapel of Ease, now St. George's Church, was at the eastern extremity of High Street, and the only other ecclesiastical building was the Presbyterian Meeting-house, on the north side of Rosemary Lane. The business portion of the town was on the north side of the Farset, or Belfast River, flowing from its source on The Squire's Hill down High Street, the estuary of which was The Dock, extending from Sluice Bridge, connecting School House Lane and Skipper Street, to The Channel where it joined the Lagan on its seaward course. The east, west and south boundaries of the Castle were reserved for the Castle Gardens, then in the full plenitude of their glory, with their formal arrangement of flower beds, Melon Garden, Robin's Orchard, Cherry Garden, an extensive plantation called the Ash Walk, the Fish Pond, and the Barge House, situated on the Castle Wharf, from which there was a canal or waterway entering the Lagan, a short distance to the south of The Long Bridge.

The beauty of the Castle Gardens had been frequently the subject of appreciative comment. Sir William Brereton, Bart., who visited Belfast on 5th July, 1635, says :--

"At Belfast, my Lord Chichester hath another dainty, stately house (which is indeed the beauty and glory of the town) where he is most resident and is now building another wall before its gates. This is not so large and vast as the other, but more convenient and commodious, the very end of the loch toucheth upon his garden and backside; here also are stately gardens and walks planted."

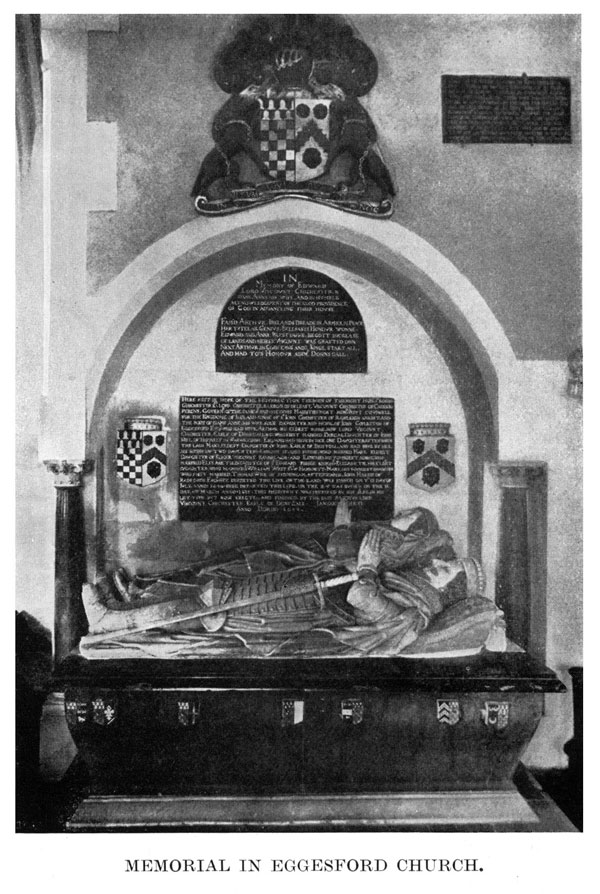

The Lord Chichester, to whom Sir William refers, was Sir Edward, brother to the Lord Deputy, who was created Baron of Belfast, to which Barony Sir Edward succeeded on the death of his brother, and was subsequently elevated in the Peerage as Viscount Chichester of Carrickfergus. He died on 13th July, 1648, at Eggesford, Devonshire, and was buried in Eggesford Church where his son, the 1st Earl of Donegall, erected a beautiful monument in memory of his father and mother.

IN

MEMORY OF EDWARD

LORD VISCOVNT CHICHESTER, AND

DAME ANNE HIS WIFE AND IN HUMBLE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF THE PROVIDENCE

OF GOD IN ADVANCING THEIR HOUSE.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

FAM'D ARTHUR, IRELAND'S DREADE IN ARMES IN PEACE

HER TUTELAR, GENIUS BELFAST'S HONOVR, WONNE.

EDWARD AND ANNE BLEST PAYRE BEGOTT INCREASE

OF LANDS AND HEIRES VISCOVNT WAS GRAFTED ONN.

NEXT ARTHVR IN GOD'S CAVS AND'S KING'S START ALL

AND HAD TO'S HONOVR ADD'D DONNEGALL.

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

HERE REST IN HOPE OF THE RESVRECTION THE BODY OF THE RJGHT HON:SR

EDWARD CHICHESTER KNT, LORD CHICHESTER BARRON OF BELFAST, VISCOVNT

CHICHESTER OF CARICKFERGVS, GOVERNR OF THE SAME AND ONE OF HIS

MAJESTIES MOST HONBLE PRIVY COVNSELL FOR THE KINGDOME OF IRELAND :

SONNE OF SR JOHN CHICHESTER OF RAWLEIGH KNIGHT AND THE BODY OF

DAME ANNE, HIS WIFE, SOLE DAVGHTER AND HEIRE, OF JOHN COPLESTON OF

EGGESFORD ESQRE WHO HAD ISSVE ARTHVR, HIS ELDEST SONNE, NOW LORD

VISCOVNT CHICHESTER, EARLE OF DONEGALL, &C. : WHO FIRST MARRIED

DORCAS, DAVGHTER OF JOHN MILL OF HONNELY IN WARWICKSHIRE ESQ. :

AND HAD ISSVE BY HER, ONE DAVGHTER THE LADY MARY, ELDEST DAVGHTER

OF JOHN EARLE OF BRISTOL AFTERWARDS : AND HAD ISSVE SIX SONNES & TWO

DAVGHTERS. JOHN, HIS SECOND SONNE BY HER, WHO MARRIED MARY, ELDEST

DAVGHTER OF ROGER, VISCOVNT RANNELAGH, AND EDWARD, HIS YOVNGEST

SONNE WHO MARRRIED ELIZABETH, DAVGHTER OF EDWARD FISHER KNIGHT.

ELIZABETH, HIS ELDEST DAVGHTER, WHO MARRIED SR WILLIAM WREY, KT.

& BARROETT. MARY, HIS YOVNGEST DAVGHTER WHO FIRST MARRIED THOMAS

WISE OF SYDDENHAM, AFTERWARDS, JOHN HARRISS OF RADFORDE, ESQ. HE

DEPARTED THIS LIFE, ON THE 8 & WAS BURIED ON YE 13 DAY OF JULY, ANNO:

1648. SHEE DEPARTED THIS LIFE ON THE 8 AND WAS BVRIED THE 11 DAY OF

MARCH, ANNO: 1616. THIS MONVMENT WAS PREPARED BY HIM SELFE IN HIS

LIFE TIME, BUT NOW ERECTED AND FINISHED BY THE SAID ARTHVR, LORD

VISCOVNT CHICHESTER, THE EARLE OF DONEGALL. JANVARY THE 11 ANNO

DOMINI, 1648.

The metrical verse, appearing on the memorial, gives a graphic, historicaI sketch of the Donegall family in its early stages :--

"First Arthur, Ireland's Dread in Armes: in Peace

Her Tvtelar Genivs: Belfast's Honovr wonne ;

Edward and Anne, Blest Payre, begott Increase

Of Lands and Heires: Viscovnt was grafted onn :

Next Arthur, in God's Cause and's King's, starts all,

And had to's Honovr, added Donnegall."

The above verse may be paraphrased as follows :-- Sir Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland, though severe in his treatment of rebels, displayed great ability in laying the foundations of prosperity, and was created Baron of Belfast. Being childless, his only son having died in infancy, and the estate being settled in tail male, he was succeeded by his brother Edward, who, having married Anne Copleston, had a large family. He was elevated in the Peerage as Viscount Chichester of Carrickfergus and succeeded by his son, Arthur, who, during his father's lifetime, was created 1st Earl of Donegall, so that, on his father's death, he became 3rd Baron of Belfast; 2nd Viscount Chichester of Carrickfergus, in addition to his Earldom. These titles are given in the Inscription on Wenceslaus Hollar's Map of Enishowen (1661). (See page 17.)

We have further testimony as to the beauty of the Castle Gardens in The Isle of Man, published in 1702 by William Sacheverell, who had been the Lord of Admiralty in the First Administration of William III. In the year 1698 he was on a voyage to I-Columb-Kill, and, through stress of weather, he was obliged to seek shelter in Carrickfergus Roads. His visit to Belfast in June of that year, is thus described :--

"I found the Earl of Donegall in town [Carrickfergus]. He received us with all the fondness and humanity that could be expected from a great man. He invited us to Bellfast, whither he was going, with the Earl of Orrery and Lord Dungannon. The Castle, as they call the Earl of Donegall's house, is not of the newest model; but the gardens are very spacious, with every variety of walks, both close and open, fish ponds and groves; and the irregularity itself was, I think, no small addition to the beauty of the place."

There is the further testimony of Bonivert, a French refugee in the service of William III, who says :--

"We landed at the Whitehouse (five days after the King)... we went that night to Belfast, which is a large and pretty town... The people very civil, and there is a great house belonging to my Lord Donegall, and very fine gardens and groves of ash trees."

That account of the garden was at the time when William III. visited Belfast, June 14-20th, 1690; and in a pamphlet, published in London, 1690, entitled An Exact Account of His Majesty's Progress from his First Landing in Ireland till his Arrival at Hillsborough, the writer, referring to Belfast, says:--

"The King found a very fine garden at the back of the Castle in which he walked previous to entering the building."

According to the Corporate Records :--

"His Majtie stayed five nights in Belfast and was very well pleased with the Inhabitants and the Towne and its cittivation and said (when within the Castle and the doors being open to ye garden) that was litle Whitehall."

Let us now picture the Castle Gardens and their surroundings at the beginning of the 18th century, from documentary evidence, both maps and leases, using as a guide Phillips' Map of 1685 as shown on page.[page no not printed] In the foreground is the Farset or Belfast River, flowing down High Street, with Chades' Bridge opposite the Market House. The small houses to the extreme right, or west, are on the site of the present Bank Buildings, where Castle Street terminated as a continuation of High Street. The thoroughfare on the near or north side of the aforesaid houses was called "The Back of the River," being on the further side from the Castle. The Castle had a north-east aspect, and opposite the entrance gates, on the east side of "the Cournmarkett ", was the Market House with its square tower, on the first floor of which, above the market stalls, was the room in which the burgesses met at their Assembly Meetings. The house adjoining on the east side of "the Cournmarkett", as the name appears on a Donegall lease of 1692, was the Castle Brew House wherein the cider was brewed from the apples gathered in the orchards. In the Great Roll of 1665-1666, there are the following items :--

"1666. Paid for gathering Apples in the Gardens and making Sider."

"Paid David Dowey for Coopradge, and for the Brew House and sellers before my Lady came home."

On the west side of the Cournmarkett, and opposite to the Brew House, was the house containing the pleasure boats in the Barge Yard, from which in a south-east direction was the Castle Wharf, joining" The New Cutt River" at the sluice, and entering the Lagan on the south side of the Long Bridge. The garden path in front of the Barge Yard, running in a south-west direction, was the Long Walk, extending the entire length of the Pleasure Garden.

The Pigeon House was the small house with the pointed roof, and in the Donegall Journal of Disbursements there is an entry, dated 11th January, 1789 :--

"Received from sundries for the old walls and the Pigeon House in that part of the late Castle Gardens, now Arthur Street, £7 1s. 2d."

Proceeding from the Pigeon House past the back of the Castle we come to the Stables, with their five dormer windows, having a carriage entrance from Castle Street. The Ash Walk, as it appears in Phillips' Map of 1685, did not extend the whole length of the Gardens. It seems, however, to have been extended, at a later date, as in a lease, bearing date 14th June, 1717, its measurement is given as 530 feet from Castle Street in a southerly direction. According to that measurement it formed the western boundary of the Castle Gardens, and was probably planted with Ash Trees as a shelter to the fruit gardens from the prevailing westerly winds. Its frontage to Castle Street was 250 feet, so that we can fix its area as three acres. To the east of the Ash Walk was Robin's Orchard, having a frontage to Castle Street and the Garden situated between Robin's Orchard and the Castle was the Melon Garden. The small building, with an entrance throngh the Melon Garden, was originally the Coach House.

The view from the gardens and the castle was, perhaps, unsurpassed for the beauty of its quiet landscape. The fertile valley through which the Lagan wended its seaward course, had as a background the hills of Castlereagh [signifying Grey Castle] with the old residence of Con O'Neill occupying a prominent position on the summit; while the slopes of the Holywood hills were visible across the twenty-one arches of the Long Bridge. The Crummuck Wood, at that time the undergrowth of the primeval forest, lay to the south, skirting the west bank of the Lagan and extending westward as far as the present Shaftesbury Square. The "Ryver of Owynvarra" meandered in its zig-zag course from the Great Bridge of Belfast, alias Brickill Bridge, alias Salt Water Bridge to its outlet at the south of the Long Bridge and, in its course, supplying fresh water to the Castle fish pond, situated at the present Arthur Square. To the west rose the Black Mountain, a basaltic range of hills, one of which is still known as The Squire's Hill, converted into a deer park by the Lord Deputy, a district now known as Oldpark with the grazing ground covered with sites for residential dwellings; and to the north arose the clear outline of Ben Madigan, with its streaks of limestone glistening in the sunshine, and the contour of its summit bearing a striking resemblance to the profile of Napoleon Bonaparte; while the trees of the New Deer Park, so-called to distinguish it from the Old Park, sloped in an easterly direction from the Cave Hill to the shores of the Belfast Lough, terminating at "Lower Wood, Lowood, or Parkmount ".

Early on Sunday morning, 25th April, 1708, the Castle was reduced to a mass of smouldering ruins and there perished in the flames the three youngest daughters, Lady Jane, Lady Frances, and Lady Henrietta Chichester; the daughter of the Parish Clergyman, the Rev. ---- Barklie, and a servant maid, Catherine Douglas; while another maid, Mary Teggart, escaped from the devouring flames. The cause of the fire is said to have been due to the carelessness of a servant who lit a wood fire in a room recently washed, and took no precautions to watch for sparks.

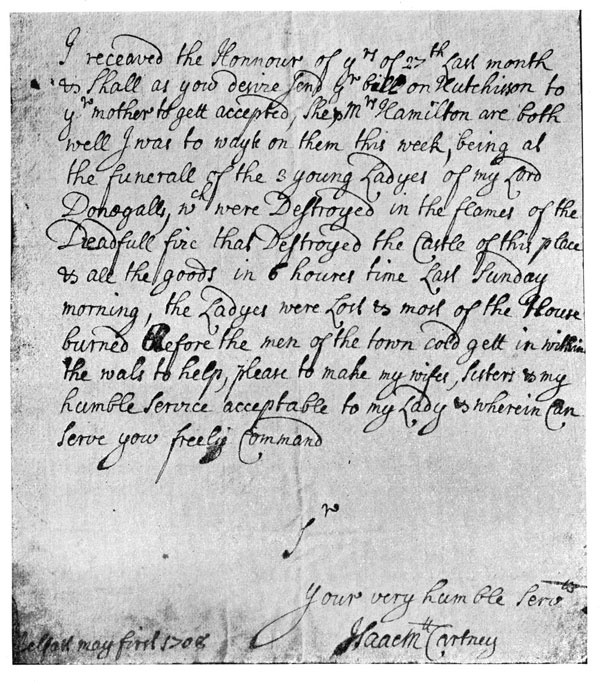

An original letter, written by Isaac McCartney, at the time of the occurrence, has been recently discovered, containing the following particulars :--

"I was to wayte on them this week being at the funerall of the 3 young Ladyes of my Lord Donegal! wch were Destroyed in the flames of the Dreadful fire that Destroyed the Castle of this place & all the goods in 6 houres time last Sunday morning, the Ladyes were lost & most of the house burned Before the men of the town cold gett in within the wals to help."

The importance of that letter is that it fixes the exact date of the fire as being Sunday, 25th April. It further states that "all the goods were also destroyed before the men of the towne cold gett in within the wals to help", and these walls, as we have already seen, were 12 feet high. Such is the account, written by a prominent Belfast resident at the time of the occurrence. Here is an artist's imaginative representation in 1896, almost two centuries later. The twelve foot walls surrounding the Castle are ruthlessly omitted; while a line of men are passing buckets of water from the Farset to extinguish the flames that, in intensity, resemble a roaring furnace. In the foreground, at the river's edge, are deposited a considerable quantity of silver plate and objets d'art, apparently rescued from the Castle. However successful the artist may have been in producing an effective drawing, it has been at the sacrifice of truth to the picturesque, and is a striking example of the danger of employing the limner's aid to depict that which the historian would refrain from expressing in words.