CHAPTER I

WHAT OUR RELICIOUS COMMUNITY HAS DONE FOR BELFAST.-Belfast in 16.p. Features of the original Presbyterianism of Ulster. Westminster Concession and Nonsubscription. Toleration and its results. Education of the Presbyterian clergy. Secession Church and its influence. New generation of Nonsubscribers. Remonstrants. Nonsubscribing Association, Footprints of our forefathers-industries - public philanthropy-literary culture-educational institutions-religious character.

![]()

ACCORDING to a sententious writer," Happy is the people that I has no History." Happy, on this estimate, must have been the condition of Belfast for a series falling not far short of 3 thousand years, beginning in the dim twilight of that legendary age, when a battle of the Farsad (A.D. 666) mingled a Celtic prince's blood with the waters of the contested Ford, and closing our reckoning with the outbreak of hostilities between King and Parliament, in the full blaze of the most exciting period of British history. To animate the vast stretch of time which lies betwixt these extreme landmarks, we have only glimpses, here and there, of imperfectly recorded contentions, for which Belfast was the occasional theatre, but in which it cannot be said to have played.yed any independent and active part.

Indeed, the Belfast of 1642 was an insignificant place, though its strategical position was destined soon to bring it into prominence.

Unprotected as yet by any wall, it consisted of a few rows of mean houses, with a small Norman fortress at one end of the main street, and a small Norman church at the other extremity. The incidents which immediately preceded the great Civil War brought to Belfast importance and Presbyterianism; the two came together.

As early as 1613, Presbyterianism had gained a footing in Ulster, on an errand of religious duty to the Scottish colonists; but it had not found in Belfast material for its purpose. The Corporation of the little town passed, in 1617, a bye-law that every burgess should attend at the Sovereign's house every Sabbath. day, and whenever there was public prayer, in order to accompany their municipal head to the parish church.

As early as 1613, Presbyterianism had gained a footing in Ulster, on an errand of religious duty to the Scottish colonists; but it had not found in Belfast material for its purpose. The Corporation of the little town passed, in 1617, a bye-law that every burgess should attend at the Sovereign's house every Sabbath. day, and whenever there was public prayer, in order to accompany their municipal head to the parish church.

To his visitation, held within the walls of that old church, in August, 1636, Bishop Henry Leslie (1580-1661) cited the five principal Presbyterian divines of Ulster. Leslie was himself of Scottish birth, yet in his opening sermon (from the ominous text, Matt. xviii. 17) he describes Scotland as "the land of Noddies," and the Presbyterian position as "this dunghill." In a two days' conference he endeavoured, with the stout assistance of the famous John Bramhall (1594-1663), then Bishop of Derry, to reduce his Presbyterian neighbours to submission by force of argument. Failing in this, he adopted another system of reasoning, with the aid of the civil power.

Five years later came the fierce insurrection of the Irish Catholics, which struck terror to the heart of the nation. An army from Scotland was despatched, by successive installments, to Ulster, in order to quell the insurgent hordes. Belfast was made secure by a wet ditch and earthen rampart (1642), and, with extreme reluctance, Colonel Chichester admitted a portion of the Scottish troops to share in the defence of the town with the English garrison. These Scottish soldiers needed the religious ministrations of a divine of their own faith. A Presbyterian chaplain, one John Baird, was appointed to come every third Sunday to our town, to conduct the simple worship of the Scottish people. The appointment was made by the army Presbytery, which first met at Carrickfergus on 10th June, 1642. Shortly after this, an eldership was erected at Belfast. So was our Church begun; this was the little seed out of which the whole Presbyterianism of Belfast has developed and grown.

Five years later came the fierce insurrection of the Irish Catholics, which struck terror to the heart of the nation. An army from Scotland was despatched, by successive installments, to Ulster, in order to quell the insurgent hordes. Belfast was made secure by a wet ditch and earthen rampart (1642), and, with extreme reluctance, Colonel Chichester admitted a portion of the Scottish troops to share in the defence of the town with the English garrison. These Scottish soldiers needed the religious ministrations of a divine of their own faith. A Presbyterian chaplain, one John Baird, was appointed to come every third Sunday to our town, to conduct the simple worship of the Scottish people. The appointment was made by the army Presbytery, which first met at Carrickfergus on 10th June, 1642. Shortly after this, an eldership was erected at Belfast. So was our Church begun; this was the little seed out of which the whole Presbyterianism of Belfast has developed and grown.

The religious system thus introduced was the Presbyterianism of Scotland of the older school, before its theology had been stiffened and dried up by the Westminster Confession of Faith. Its principles of faith and statement of public policy are admirably expressed in the Solemn League and Covenant (A.D. 1643), which pledged all who took it to endeavour the reformation of religion throughout the three kingdoms "in doctrine, worship, discipline, and government, according to the Word of God and the example of the best reformed churches." Copies of this noble document were brought to Ireland very soon after it was drawn up. Lying in a drawer at our Museum in College Square is one of these first copies, which somehow escaped the hangman's hand and the vengeful fire of 1661. It still bears its 67 original signatures, collected at Hollywood on 8th and 9th April, 1644, by William Adair, who came from Scotland for the purpose. Among the names is a John M'Bryd, possibly the father of the outspoken John M'Bride who ministered here fifty years later.

It was this league of faith, with its stern opposition to Popery and Prelacy, its direct reliance upon the Bible as the Word of God, and its noble protest on behalf of "the common cause of religion, liberty, and peace," -- it was this, and not the Confession of the Westminster divines, which really formed the religious mind of the first Presbyterians of Ulster. This was what they subscribed, when they subscribed at all. At a later day (1705) they did indeed enact subscription to the Westminster Confession, in a panic raised by the daring heresies of Emlyn. Yet the enactment was not, and could not be, rigidly enforced. Throughout the last century, and indeed up to the year 1836, it was found impossible to secure in Ireland, even on the part of orthodox men, the subscription which was accepted in Scotland as a matter of course.

Many things contributed to this freer attitude of the Irish offshoot from the religion of Scotland. It never enjoyed the privileges or wore the fetters of an Establishment, and was free to develop in its own fashion. During the Commonwealth, it had to give way to Independency; and this broke, to some extent permanently, the hold of its ecclesiastical discipline, The depression of its power came about in this wise. On the execution of the King, the Presbytery at Belfast protested against the trial and its issue, in the strongest terms they could use, as "an act so horrible, as no history, divine or human, ever had a precedent to the like." Thereupon, Cromwell's Latin secretary, John Milton, assailed them with that vituperation of which, as well as of the divinest poetry, he was so great a master, calling them "blackish presbyters of Claneboye," "that un-Christian synagogue of Belfast," and "a generation of Highland thieves and redshanks." Cromwell's officer, Venables, expelled them, along with (it is said) 800 of their hearers; and William Dixe, a Baptist preacher, was set to minister to those inhabitants of the town who were not Episcopalians.

It must further be remembered that the Scottish type of Presbyterianism was not the only one which had found its way into Ireland, Scotland furnished, with few exceptions (e.g., at Antrim), the Presbyterianism of Ulster; but in Dublin and the South of Ireland it was the English type of Presbyterianism, freer both in doctrine and discipline, which gained an entrance. Its existence there had an indirect influence on the severer views and ways of the North. Nay, in Belfast, the influence of English Presbyterianism was direct. Letitia Hickes, who became Countess of Donegal, was an English Presbyterian. William Keyes, who stands first in the uninterrupted succession of our own ministers, was an English divine under her patronage. Sore was her displeasure when his congregation and co-presbyters permitted him to leave for Dublin; many the obstacles placed in the way of the appointment of a Scottish divine as his successor, though that Scottish divine was no less distinguished a man than Patrick Adair. She would not attend his services. In the Hall of the Castle, Samuel Bryan (contemporary with Keyes) and Thomas Emlyn (contemporary with Adair) successively officiated as chaplains. Bryan had been Fellow of Peterhouse, and held a Warwickshire living until the Uniformity Act of 1662 compelled even moderate men, possessed of consciences, to quit the Establishment. Half-a-year's incarceration in Warwick gaol, for the crime of preaching the Gospel at Birmingham, had induced him to leave his native land. Emlyn was so far from ever sympathising with the Scottish peculiarities of Presbyterianism, that, while resident in Belfast, and still retaining intact the Puritan theology, he held no communion with Adair, but willingly preached by invitation in the parish church, the then Vicar, Claudius Gilbert, being an ex-Dissenter, Thus, in Belfast, there was present in very early times, side by side with the Scottish discipline, the mellowing influence of a type of Nonconformity less severe.

Nor must it be forgotten that the delay of legal Toleration to Irish dissent brought with it a compensating advantage of the highest moment. Toleration in England, granted in 1689, was made dependent on subscription to the doctrinal articles of the Established Church. Toleration in Ireland, not granted till 1719, was given at length to all Protestants without any doctrinal stipulations whatsoever, except the oath against transubstantiation, and a clause directed, not against those who abandoned, but against those who impugned, the doctrine of the Trinity, This was indeed a greater freedom than the Presbyterians had themselves asked for, or dreamed of. They had drawn up certain doctrinal clauses, milder than the English articles, to be inserted in the Bill, Tradition says that King George I., "upon receiving the proposals of the Irish ministers," struck out the doctrinal clauses with his own royal hand, saying, "They know not what they would be at; they shall have a toleration without a subscription:'

In other respects, indeed, Presbyterians were not free. They could not celebrate marriages among themselves, at least not without incurring severe penalties in the ecclesiastical courts. They could hold no public office, except on the condition of communicating at the Established churches. But the law laid no pledges upon them as regards the doctrines they were to accept as their bond of union, or to teach in their meeting-houses.

Hence, in Ireland, the position of the Nonsubscribers was perfectly legal from the first, which it never was in England till the Relief Act of 1779. When Haliday, on being installed in 1720, the very year after the Irish Toleration Act, refused to subscribe, it was at once plain that a movement of far-reaching importance was begun. He set an example which was soon followed. Seven successive Synods took the matter up, being plainly at a loss what to do. At last the advocates of the Westminster standards hit upon the notable expedient of gathering all the Nonsubscribing men into one presbytery. It was easy to do this, for they were men who had already set on foot a union among themselves, having been accustomed for twenty years to meet for purposes of Biblical study under the name of the Belfast Society (1705). The members of this society were formed into the Presbytery of Antrim (1725). Next year, this body was expelled from the Synod, neck and crop.

The deed was deftly done. But the members of the expelled Presbytery were the ablest men of the Presbyterian body. Their influence was perpetually being reinforced, and their example tacitly followed, by the more educated men in the Synod itself. In those days, and for long after, the great place of education for the Irish Presbyterian ministry was Glasgow College. And the leading professors of Glasgow were prevailingly New Light men. John Simson, Professor of Divinity, was censured for alleged Pelagianism (1717), and deprived of ecclesiastical recognition for alleged Arianism (1728), but was not removed from his chair. Francis Hutcheson (1694-1747) the philosopher, himself an Irish Nonsubscriber, and William Leechman (1706-1785) the divine, taught the Irish students to think for themselves on the highest subjects.

Until the Seceders came from Scotland, shortly before the middle of the last century (1742), the general spirit and tone of Irish Presbyterianism was moving in the line marked out by the Nonsubscribers. At the end of the century, out of fourteen Presbyteries, only five exacted subscription. The Seceders, however, began that reaction towards the doctrines of the Westminster Confession which it took almost a hundred years to accomplish, and which gained no very decided victory until the issue of the momentous conflict between Henry Cooke (1788-1868) and Henry Montgomery (1788-1865) was reached in the voluntary withdrawal of the Remonstrants (1829). Even Dr. Cooke did not succeed in carrying an unqualified subscription to the Confession of Faith till seven years after the Remonstrants had left the Synod, At five o'clock on the morning of Friday, 12th August, 1836, the wisdom of Westminster carried it by a large majority against the Word of God. Four years later was accomplished that union between the Synod and the Seceders which set the seal upon the reaction against the true genius of Irish Presbyterianism, and formed the present General Assembly (10th July, 1840).

The new generation of Nonsubscribers, the Remonstrants who withdrew from the Synod of Ulster, were influenced in their withdrawal by doctrinal considerations much more direct and radical than those which had produced the expulsion of the Antrim Presbytery over a century before. They did not amalgamate with the earlier body, preferring to constitute a separate Synod of their own in 1830; but in a few years they entered with the Antrim Presbytery into an Association for mutual protection and aid, which embraced also the Nonsubscribers of the South, known as the Synod of Munster. This Association of Irish Nonsubscribing Presbyterians (1835), which in the eye of the law, and according to ecclesiastical discipline, comprises four distinct, though cognate, Presbyterian bodies (besides two independent congregations, admitted in 1872 to share the elastic name "other Free Christians"), is the only organisation which has any claim to represent the whole community of Nonsubscribing Christians in this country. [The representation is not quite complete, since there are one or two congregations not in the Association.]

What, from first to last, has this body done for Belfast? We have seen that the rise of Belfast into significance was due to its becoming a stronghold of the Presbyterian army before the Civil War. Will anyone call this a simple coincidence? It is impossible so to dispose of the story of the subsequent growth and greatness of our town. The development of Belfast, material, intellectual, and moral, has been not merely coincident with, but dependent upon the enterprise, the public spirit, the culture and acquirement, the stable character of its Presbyterian inhabitants.

We, as a church, may not unfairly claim to hold a representative position ill regard to the Presbyterianism of Belfast.

We may put forward this claim on historical grounds. Our congregation is the mother church of Belfast Presbyterianism; for two generations it was the one focus of Presbyterianism in the town. The older divines of our ministry, and the original leaders or our staunch laity, are owned and revered by the whole Presbyterian community around us, accepted as being their founders quite as much as they were ours. Patrick Adair (1625?-1694) and John M'Bride (1650-1718) and James Kirkpatrick (1674?-1744) belong to us; but they are the men who paved the way, not for us alone, but for Presbyterianism generally. On one of our alms-dishes is inscribed the sentence --

We may say of the Presbyterian faith and strength that these also are the gift of our ancestors, under God, to "all the Meetinghouses in Belfast."

In another and a broader sense we may make this claim. The spirit which has made Presbyterianism valuable, not only as a protest against Popery and Prelacy, but as a noble and powerful influence on the side of culture, philanthropy, the beneficent progress of civilisation, and the faithful and charitable life of pure religion, is the spirit which has been persistently fostered by the ministry and exemplified by the laity of this church.

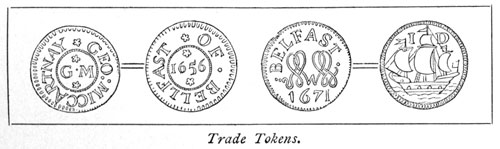

Look through the history of Belfast; watch the growth of its trades and manufactures. From the Presbyterian potters of 1693, the Presbyterian ship-carpenters of 1712, and the wealthy Presbyterian merchants a little later, down to the leaders of industrious enterprise at the present day, we trace one unbroken line of able and far-seeing men, the hand of whose diligence has made rich the town whose prosperity they have created. No inconsiderable proportion of these men, whether we speak of numbers or of leading power, has been contributed by the membership of our church. Study the lists of the founders of our successive linen-halls; the names of our bankers and merchants. since banking and merchandise began in Belfast; of the originators of our Chamber of Commerce, established in the same year in which our meeting-house was rebuilt Among the prominent names, not the least prominent are names which figure also in the roll of our own congregational constituency.

If we speak of philanthropy, and inquire for the originators of hospitals general and special, of charitable institutions old and new, for the good of the many without reservation to the disciples of a creed, the result of our investigations is to bring us again and again to Rosemary Street for the religious impulse which had inspired the deed of wise and in unexclusive charity. In such operations of applied Christianity, individuals from among us have been ever ready to show the way. By the general contributions of our people, whether given privately or acting as a church, such projects and organisations of benevolence have always been generously supported. What is infinitely more, our people have never been slow to dedicate thought, care, time, zeal, energy, out of the abundance of an unselfish determination to promote, by every means in their power, the amelioration of the lives Turn we to the annals of our local literary renown. The leading printers and publishers of Belfast, from Neill and Blow down to Joy and Hodgson, and later but not less distinguished names, were Presbyterians of the Nonsubscribing freedom.

Professor Witherow, of Derry, has published two most interesting volumes of .. Historic and Literary Memorials of Presbyterianism in Ireland" (1879 and 1880). These were placed not long ago in the hands of a gentleman not of our body, and in returning them to the lender he remarked. "How is this? Nearly all these men, these writers and divines, were Presbyterians of your sort." "How is it?" was the reply. "Why, it is this way. If the book was to be written at all, it must be filled with our men and their works, for there are no other materials to make a book with." So of that later literary circle which gave to Belfast the name of the Athens of the North of Ireland. Its chief ornaments were men and women of genius and culture, bred in the bosom of our own religious community.

If we think of the educational institutions, large and small, which have fostered in Belfast and throughout Ulster the spirit of learning and of science, to whom must we ascribe their rise and their fame? The pioneers of educational advance, from David Manson onwards, the founders of the Academy, the professors and teachers who gave tone to the Academical Institution, the originators of Sunday and daily schools (or the neglected classes; who were they? The roll of our membership will largely tell.

Could you tear from the history of Belfast the names and the influence of our forefathers, distinguished in commerce, learning, philanthropy, education, and genius, you would not only remove the pages inscribed with some of our most eminent and best citizens, but you would find that you had drawn out as well the inspiring examples which have been a source of power and of impression, extending far beyond the limits of the small community which they illustrated.

Yet it will perhaps be said, 'All this is not religion.' There arc some people, it would appear, who think that effects may be produced without the existence of causes: that the highest results can come without the operation of the highest influences; that works may be originated and sustained and live, without faith as their basis; that you may have all the finest fruits of the activity of the human mind and spirit and life, and be entitled nevertheless to say, 'There is no religion, in it or under it.' The outcome of the practical life of a community discloses what the substance of its moral ideal, and what the nature of its religious faith and spirit, really are. We shall trace the inner history of the religion of our forefathers in subsequent chapters of this volume; at present we are contemplating it in its powerful and beneficent outer working. If, to-day, we are "citizens of no mean city," it is largely because we are inheritors of no mean traditions, fostered by the faithfulness of the founders and maintainers of this and kindred churches.

In the Belfast of to-day we are, in one sense, outnumbered and outweighted; the masses are not with us. Yet we occupy a unique position, neither unimportant nor inglorious, and we cannot help doing so. We are the heirs and administrators and assigns of the true original Presbyterianism; of its liberty, its learning, its broad and beneficent aims. God, not we, has placed us where we are. He who planted the heavens, He who laid the foundations or the earth, it is He, and He only, who hath put into our mouths His words: who hath kept us, throughout our course, in the shadow of His hand: and who saith to us now, by the voice of His Spirit, "Thou art my people" (Isa. Ii. 16).

DATES. -- Introduction of Presbyterianism in Ulster, 1613; in Belfast 1642. westminster Confession published, 1648. Sacramental Test Act, 1704. Synod orders subscription to Westminster Confession, 1705. Belfast Society, 1705. Toleration Act, 1719. Haliday refuses to subscribe, 1720. Antrim Presbytery (Nonsubscribing) formed, 1725; excluded from the General Synod, 1726. Dissenting Marriages allowed, 1738. Seceders came from Scotland, 1742. Test Act repealed, 1828. Remonstrant Synod, 1830. Association of Irish Nonsubscribing Presbyterians, 1835.