CHAPTER II

HISTORIC LANDMARKS IN THE CAREER OF OUR OWN CONGREGATION. Our successive places of worship -- North Street -- Rosemary Lane; off-shoots from us; public buildings of Belfast in 1783. Our trusts and title deeds; Dissenters' Chapels Act. Our Ecclesiastical Changes -- General Synod -- Antrim Presbytery -- Northern Presbytery of Antrim. Personnel of our ministers and laity. Congregational resources -- Regium Donum -- disestablishment. Our position at the present day.

![]()

IN the oldest authentic map of Belfast, a sketch-plan drawn by Thomas Phillips in 1685, there is figured at the north-west extremity of Hercules Street (removed in 1883 to form the Royal Avenue), in close proximity to the North Gate, a small building without chimneys, which, as some fancy, represents the original Presbyterian Meeting-house of Belfast. Tradition assigns to the first structure erected as a home for Belfast Presbyterianism a site near the gate just mentioned, but wavers between North Street and Hercules Street as the precise thoroughfare on which it stood, Inasmuch as these streets converged upon the North Gate, the building depicted on the map may be thought to answer, fairly well, to the conditions of locality implied in the floating tradition.

When was it erected? There is no trace of any meeting-house in Belfast prior to the Restoration of the monarchy, When the Presbyterian system was introduced, in the manner described in the previous chapter, we may take it for granted that, as was usual, its worship was held in the old Parish Church at the foot of the High Street. But now comes a curious episode in the religious history of our town. For seven years (1649-56) during the Cromwellian occupation, after the 800 Scots had been driven from the town, and the Independent régime was in power, there was no available house of prayer of any kind within this borough. The old church and its graveyard were converted into a citadel and fortification; and where the people worshipped we cannot tell. An Episcopalian preacher and a Baptist preacher were maintained at the public expense, and they must have conducted their ministrations in casual places, or in the open air. More than once the municipal authorities of the little town addressed the Council of State, begging for the restoration of their church; or, if not, requesting that public meeting-houses might be provided. The church was at length given back, in a ruinous condition, and appears to have been then treated as a "Publique Meeting Place" for the religious use of all sects. When the Restoration came (A.D. 1660), we find it in the hands of the Presbyterians, though apparently not devoted to their exclusive use. But, with the King, came back the Bishops.

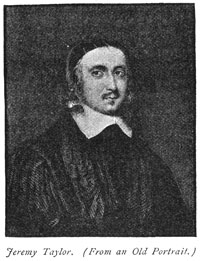

Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667), the new Bishop of Down and Connor, was a startling illustration of the maxims that circumstances alter cases, and that preaching and practice are different things. Jeremy Taylor, dwelling in a Welsh exile, his living of Uppingham having been sequestered because he had joined the army against the Parliament, composed and printed his Liberty of Prophesying (1647), a classic defence of the rights of conscience. Jeremy Taylor, promoted to an Irish Bishopric, at once assumed to himself the liberty of putting down all prophets who did not happen to be in Episcopal orders. Three months after his consecration (1661) he, in one day's visitation, cleared the Presbyterians out of 36 churches in his diocese. We are told, in Jeremy Taylor's funeral sermon by George Rust, his friend and successor, that "this great prelate had the good humour of a gentleman, the eloquence of an orator, the fancy of a poet, the acuteness of a school man, the profoundness of a philosopher, the wisdom of a chancellor, the sagacity of a prophet, the reason of an angel, and the piety of a saint." It should have been added, to make the picture complete, that he had the bowels of a bumbailiff. In England, the Presbyterians were not ejected as such, until the State had passed the Act of Uniformity of 1662. In Ireland, the Bishops took time by the forelock, the legislature followed suit, and Taylor was the man who, by his prompt work in his diocese, and by his sermon before the two Houses of Parliament, both showed and led the way.

Hence it was that, in 1661, the Presbyterian worshippers of Belfast found themselves homeless. Some time afterwards, we cannot tell exactly when, but it was probably in 1668 (so we gather from Adair's Narrative), they erected their first meeting-house, near the North Gate. In the manuscript Minutes of the "Antrim Meeting," under date 3rd March, 1674, John Adam, merchant, appears as a commissioner from the Belfast congregation (then without a minister), to petition the brethren to make interest with Lord and Lady Donegal on two points; and one is "anent the House of Worship," in regard to which the Meeting appointed two brethren humbly to represent to the peer and peeress "what weighty reasons make for the people having their liberty as other congregations have, without irritation so far as possible." The inference is that the Meeting-house was in being, but that the use of it was in some degree controlled by the great people at Belfast Castle.

But what has that long-perished building, on a forgotten site, to do with us to-day? Here are we in Rosemary Street, by help of our good M'Bride. On this pleasant spot of ground he planted us, when it was an open field, abutting upon a crooked lane, with the scent of rosemary still about it, and leading to the backs of the houses in another lane, which bore originally, it is believed, the name of Ardglass, later dignified into the mythological title of Hercules, M'Bride knew his way to the favour, if not to the sympathies of the Earl of Donegal, and secured for us this queer, triangular piece of land, which stands so invitingly vacant on the map of 1685. Here, on the green sward of the meadow, an oblong structure arose. An excrescence to the west gave it the shape of a T; but there were outside stairs to the three galleries, which varied the configuration of its exterior; and, at the north-east corner, there was a small session-house, stuck on to the main building. In the south-west angle of the field, a minister's dwelling was put up for the worthy M'Bride; and there, except when his refusals to lake the oath of abjuration forced him to flee to Scotland (a circumstance which took place no less than four times), he had his abode. His successors occupied the same premises until Crombie's time, in fact till the building of the Academy (1786).

The occupancy of the Rosemary Street property by the Presbyterian congregation may be dated from about 1695; but there is no trace of any lease or legal document giving a title to it, either then or for long after. In fact, it would have been impossible to have executed a legal conveyance for the benefit of Presbyterians, while they remained untolerated in the eye of the law, existing only upon sufferance, and much better protected in their position by the good-will and pleasure of a powerful Earl, than by a trust which the courts would not recognise, But in 1767, when Toleration had been granted some forty-eight years,  Arthur, Earl of Donegal, afterwards the first Marquis, gave us a lease. It begins by reciting that "the said Arthur, Earl of Donegal, is minded and desirous, that the said first congregation of Protestant Dissenters shall and may, at all times hereafter, have and enjoy a certain place in his town of Belfast for the publick worship of Almighty God, and that the minister of the said congregation for the time being may be provided with and enjoy a messuage or tenement, near the same, for his better accommodation;" then, after describing the buildings, and appointing the trustees (R Gordon, Joseph Wallace, and John Galt Smith), it grants to them the same "for the uses, intents, and purposes hereinafter mentioned. . . and for no other intent and purpose whatsoever." These uses and intents, as relates to the Meeting-house, . . . are simply as follows: "and that the said building, now used as a Meeting-house, may continue and remain as and for a publick Meeting-house for the use of the said first congregation, and their successors, for ever."

Arthur, Earl of Donegal, afterwards the first Marquis, gave us a lease. It begins by reciting that "the said Arthur, Earl of Donegal, is minded and desirous, that the said first congregation of Protestant Dissenters shall and may, at all times hereafter, have and enjoy a certain place in his town of Belfast for the publick worship of Almighty God, and that the minister of the said congregation for the time being may be provided with and enjoy a messuage or tenement, near the same, for his better accommodation;" then, after describing the buildings, and appointing the trustees (R Gordon, Joseph Wallace, and John Galt Smith), it grants to them the same "for the uses, intents, and purposes hereinafter mentioned. . . and for no other intent and purpose whatsoever." These uses and intents, as relates to the Meeting-house, . . . are simply as follows: "and that the said building, now used as a Meeting-house, may continue and remain as and for a publick Meeting-house for the use of the said first congregation, and their successors, for ever."

This is what is called an "open trust;" a more open one is scarcely possible. But, prior to the Dissenters' Chapels Act of 1844, open as the trust is, the building would have been tied up in law to the precise opinions and modes of worship held and practised by its original founders; the silent voice of the men of 1767 (perhaps of 1695) would have been entitled to decide the faith and to rule the usages to which the building could be devoted to-day. Moreover, even if it could be proved that the founders of an old meeting-house were actually Anti-trinitarians in their faith, the lawyers would say: 'That was, at the time of the foundation, an illegal profession, prohibited by statute; and a trust for the maintenance of such an opinion is void in law.' The Irish Toleration Act (as we saw in the previous chapter) did not exclude Anti-trinitarians, but it forbade them to open their mouths against the doctrine of the Trinity. However, the Dissenters' Chapels Act swept away both classes of restriction. It provided that all opinions, which had since become legal, were to be regarded as legal from the first. It substituted for the opinions of the founders the unbroken usage of twenty-five years. Any opinion, which had held its ground in a Dissenting meeting-house for a quarter of a century, undisputed at law, was fully legitimised, unless there were any express provision in the trust deed which excluded it.

In the obtaining of this salutary measure of relief and freedom, services of the first rank were rendered by one who, we may be proud to think, was long a seatholder and always a warm friend of this house; the mighty, the eloquent, the indomitable advocate of truth and justice, Henry Montgomery, who sacrificed time, health, and overwhelming energy in the common cause. It was no unreal danger from which he and his able coadjutors delivered us. The placid pages of our congregational Minute-book, at the period of the passing of the Bill, quiver with the agitation of that momentous struggle. No wonder the leaders of the congregation were alarmed. Clough and Killinchy had trusts as open as our own; but the law was set in motion. "The enthusiasm of orthodox solicitors," as has been well said, was "associated with the rapacity of acquisitive divines;" and the Meeting-houses of Clough and Killinchy, ruthlessly taken from their owners, were given to the men who subscribed the Westminster Confession and forgot the eighth commandment. The enemies of our faith, nay of our very existence, were confident of expelling us also from the sanctuary of our fathers, and were filled with elation in the hope of humiliating and even of crushing us. They had already their plans devised, for the disposal to their own uses of our sacred property, as soon as they had wrested it from our hands. They did our Meeting-house the honour of thinking that (after being subjected, of course, to suitable lustration) it would serve exceedingly well as a hall of assembly for the General Synod. Well, peace be to the memory of those old strifes! Let us rather recollect the combination of noble minds, the ornaments of our supreme legislature, who, in no party spirit, and indeed acting together with a total disregard of the restraints of party, carried the measure of liberty and safety which secured us in the tranquil possession of our own. Peel and Lyndhurst, Russell and Gladstone, Macaulay and Shiel -- never should we lose a grateful sense of what we owe to their disinterested and persevering support. There is perhaps no speech in the English language more withering in its sarcasm, more grand in its glow, than the speech of Shiel, the Roman Catholic, for justice to the Unitarian.

Ten years after the passing of the Act, our congregation acquired the fee-simple of the estate on which its buildings stand. The Meeting-house and the site of the old manse are thus absolutely our own; the area which surrounds both Meeting-houses we hold in common with our neighbours of the Second Congregation. The carrying out of this improved arrangement we principally owe to the foresight and the business power of our honorary secretary. Never was congregation better served, or with a warmer and stronger regard to all its best interests, than this congregation has been, for the past forty-six years, by George Kennedy Smith, the representative of the oldest of our families. His Minute books are models of what such records should be, and will remain to future ages a permanent monument of well-directed zeal and scrupulous care; his administration of our affairs has proved him sound in judgment, firm yet patient of purpose, young in heart.

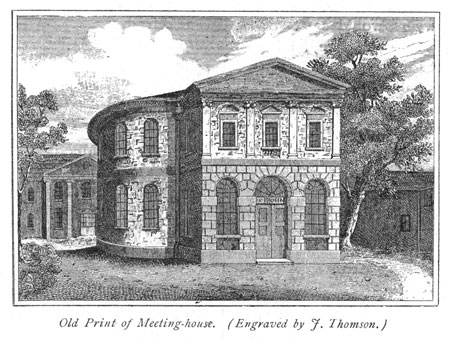

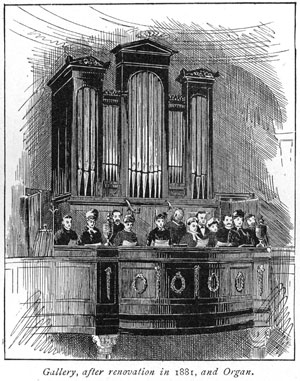

Our oldest existing record is the Funeral Register (1712-36); but its entries do not refer exclusively to our own congregation, or even to the Presbyterian burials of Belfast alone. The final volume of our Baptismal Register was lost before 1790; the second volume opens in 1757. Our Congregational Minutes begin in the year 1760, with the proceedings of a meeting which added to our constitution a Committee, as distinct from the Session. Twenty-one years later, the Minutes record the first steps taken with regard to the rebuilding of the Meeting-house. On Sunday, 1st April, 1781, the congregation resolved that the old building should be taken down. Its materials sold for £200 10s. 9d. On Friday, 1st June, the foundation stone of the present structure was laid. Exactly two years were occupied in its erection and completion. On Sunday, 1st June, 1783, it was opened for public worship. Our Minute-books are full of entries which prove how completely the superintendence of the work was a labour of love, and how minutely it was looked after, even to the tempering of the mortar. The treasurer of the Building Fund, Mr. John Galt Smith, was so deeply interested in the progress of the work, that he watched the laying of each successive course of the masonry.

Originally it had been intended that the new building should be somewhat of the old type, but without galleries, and with accommodation for 600 on the ground floor (the old building, with its three galleries, seated 723). On 12th May, 1781, the Building Committee decided on the elliptical figure, and new plans were accordingly prepared by the architect and contractor, Mr. Roger Mulholland. Francis Hiorn, the London architect of St. Anne's, took a great interest in the structure, and furnished valuable suggestions, especially as regards the pewing of the interior. With a view to improve the appearance, a gallery was decided upon, with some misgivings as to whether it would be required, and, by a sort of prophetic anticipation, a part of it was already called the "organ gallery," though no organ was erected in it till February, 1853.

Originally it had been intended that the new building should be somewhat of the old type, but without galleries, and with accommodation for 600 on the ground floor (the old building, with its three galleries, seated 723). On 12th May, 1781, the Building Committee decided on the elliptical figure, and new plans were accordingly prepared by the architect and contractor, Mr. Roger Mulholland. Francis Hiorn, the London architect of St. Anne's, took a great interest in the structure, and furnished valuable suggestions, especially as regards the pewing of the interior. With a view to improve the appearance, a gallery was decided upon, with some misgivings as to whether it would be required, and, by a sort of prophetic anticipation, a part of it was already called the "organ gallery," though no organ was erected in it till February, 1853.

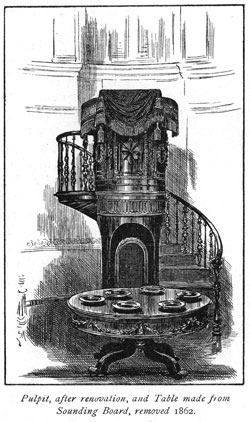

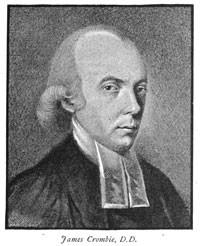

The total cost of the new structure was £1,923 7s. 9d., British currency. Towards this, Dr. Crombie gave a donation of 10 guineas, and lent a sum of £276 18s. 51/2d. (£300 Irish), which is an indication that he had private means; his stipend was never more than £110 15s. 41/2d. (£120 Irish), but then he had a Manse and Regium Donum, though Regium Donum in those days did not amount to £10 a-year. The Bishop of Derry (Earl of Bristol) sent a donation of 50 guineas, purely out of admiration of the beauty of a building which, as his letter to Mr. Rainey Maxwell expressed it, "does equal honour to the taste of the subscribers and the talent of the architect." Among other ways of raising the requisite funds, the Committee bought for £5 15s. 43/4d. a lottery ticket, "which was a blank." The pulpit, costing £27 18s.4d., was presented by the ladies of Belfast, irrespective of creed. In this pulpit, in 1789, John Wesley preached. He minutely describes the building in his journal, calling it "the completest place of worship I have ever seen." He would have preached a second time, but on the first occasion the crowd swarmed all over the building, and in the commotion some unconverted hearer managed to abstract the silver rim and clasp from the pulpit Bible, so the Trustees declined to grant their Meeting-house again to the great evangelist.

To Crombie we largely owe it that we continue to exist at all as a separate congregation. For there were those who thought, until his courage and determination reassured them, that it was needless for the First Congregation to have a Meeting-house of its own, and that it might fitly be wiped out of existence by reamalgamation with its eldest offshoot in the Second House.

That first swarming out from the old hive took place in 1708, and simply meant that at that date, with 3,000 Presbyterians in Belfast, one Meeting-house was not big enough to accommodate them. The two congregations were, for a time, practically one. Even when they agreed to be distinct, the stipend, £146 13s. 4d., continued to be collected in common, and was equally divided. They still share the property of the ground above referred to, and the use of the same cups [figured page 17] for the administration of the communion.

That first swarming out from the old hive took place in 1708, and simply meant that at that date, with 3,000 Presbyterians in Belfast, one Meeting-house was not big enough to accommodate them. The two congregations were, for a time, practically one. Even when they agreed to be distinct, the stipend, £146 13s. 4d., continued to be collected in common, and was equally divided. They still share the property of the ground above referred to, and the use of the same cups [figured page 17] for the administration of the communion.

The second offshoot from us was of a different and less harmonious character, due to the disputes upon ecclesiastical freedom, which soon produced their usual result in doctrinal differences; and these, as is too often the case, led to an almost complete estrangement and alienation. This double series of divergences between our point of view and that consistently maintained by the Third Congregation, since its origin in 1721, will be considered in the next chapter.

Let us, before we pass from the subject of the successive religious edifices which have arisen on or near this spot, recall the interesting fact that 1783 was not far from the culmination or an important building period in Belfast. The oldest public building still remaining in this town is the Old Poor House. crowned by the most elegant of our spires; its foundation stone was laid in 1771. Next came the Brown Linen Hall, in 1773; then the Parish Church (St. Anne's), begun in 1774; and just on the very day (28th April) in 1783 when this Meeting-house was so far finished that the congregation were invited to fix upon their sittings, the first stone of the White Linen Hall was laid with much ceremony. In 1784 Donegal Place was projected, as a grand new quarter for the residences of the rich, cutting through the Castle Gardens, in which King William delighted during his short visit to Belfast. It took almost a hundred years to bring our citizens to the point of extending this handsome thoroughfare on the other side of Castle Place, for purely business purposes.

But we must not bury the larger interests of our subject beneath questions of architecture or heaps of bricks and mortar. This congregation has passed through changes more important than those involved in the transference from the North Gate to Rosemary Lane, or from edifice to edifice. Briefly let us review our ecclesiastical changes. Our first home was in the Antrim Meeting, and when this expanded into the General Synod (A.D. 1690), we were connected with its Belfast Presbytery. We did not leave the General Synod; it drove us out. It treated us very much as Jeremy Taylor had treated us two generations before. He had said, "Conform or quit." The Synod said, "Sign or be off." To Jeremy Taylor we had replied, ''We shall not conform, and we shall not go. You may put us out of the Parish Church; but you can neither exclude us from the Church of Christ, nor from the town of Belfast. We are Christians, we are citizens, and we mean to live." Precisely the same answer did we render to the General Synod: "We shall neither sign nor decamp. Once more you may cause us to suffer expulsion from church courts; we can bear it. It is in your power to gather up your skirts and renounce connection with us. You cannot cut us off from that which alone makes church courts desirable. We stay here, in the name of God and in the strength of Christ, a witness for faith in freedom."

But we must not bury the larger interests of our subject beneath questions of architecture or heaps of bricks and mortar. This congregation has passed through changes more important than those involved in the transference from the North Gate to Rosemary Lane, or from edifice to edifice. Briefly let us review our ecclesiastical changes. Our first home was in the Antrim Meeting, and when this expanded into the General Synod (A.D. 1690), we were connected with its Belfast Presbytery. We did not leave the General Synod; it drove us out. It treated us very much as Jeremy Taylor had treated us two generations before. He had said, "Conform or quit." The Synod said, "Sign or be off." To Jeremy Taylor we had replied, ''We shall not conform, and we shall not go. You may put us out of the Parish Church; but you can neither exclude us from the Church of Christ, nor from the town of Belfast. We are Christians, we are citizens, and we mean to live." Precisely the same answer did we render to the General Synod: "We shall neither sign nor decamp. Once more you may cause us to suffer expulsion from church courts; we can bear it. It is in your power to gather up your skirts and renounce connection with us. You cannot cut us off from that which alone makes church courts desirable. We stay here, in the name of God and in the strength of Christ, a witness for faith in freedom."

Thus did we take our stand, cheerfully, with our brethren of the Antrim Presbytery, who preferred the simple dignity of serious conviction to the orthodox repute of a religious bondage. If anyone ask why, twenty-three years ago, this congregation severed the longstanding tie which had united it in happy union with the Antrim Presbytery, and entered a second time, after 136 years, into a new ecclesiastical connection, the answer is, that this step was only taken as the issue of a deep and deliberate assurance that it was necessary again to bear testimony to the vitality of the religious convictions which underlie our freedom. The Northern Presbytery of Antrim, to which we now belong, is the child of controversies of which the immediate soreness has passed away. On either side men were in earnest, and had the courage of their conclusions; and, where men are in earnest, they will respect each other sooner or later. We have no quarrel with our old friends of the Antrim Presbytery, though in our new ecclesiastical relation we put prominently forward, as we think to be right and demanded by the times, a principle which they deem it unnecessary to embody in the terms of their corporate union, viz., that without faith in Christ and in Revelation, our ministry would be a mockery, our position a snare.

It remains to say a few words respecting the distinguished line or ministers who have been the pastors and teachers of this church. Advance, then, from your dim and distant shades, ye fearless leaders of our people through dark and perilous hours. John Baird, Anthony Shaw, and Read, what know we of you but your names? Your gifts and talents, your deeds and hopes, are covered o'er with the impenetrable shroud of time. But ye were the first in this cause. Others have tended and spread the flame; yours were the hands which lighted the lamp. Come, William Keyes, from thy southern retreat, and tell us whether Dublin to which thou didst betake thee, or Belfast which thou didst leave, now pleases thee best. We have learned some freedom since thy days. The old Covenanting spirit, perchance too stern for thee, is in us still. As in our first youth as a people, so today, we shall not yield or flinch, falter or give way, where truth or duty calls. But there is a leaven among us, so we trust, of patience and of charity, which has worked some changes in our temper, without impairing the force and fulness of our spirit. Rise, Patrick Adair, pillar of our ancient strength; historian, diplomatist, trusted of Kings and beloved of thy people; shrewd and strong at the council board, and most melting preacher. Read in the fortunes of thine old flock some further pages of the Narrative thou didst begin; and say, Wilt thou reject us, who have followed thine instructions in their power and spirit, rather than copied the fashion and the mould in which thy living thought ran freely in its day? Once more let us look upon thee, honest John M'Bride, tart of tongue, tender of conscience, with the work of God in thy heart, and with no fear of man before thine eyes.

Thy jolly visage on our Vestry wall tells us more of thee than all thy sermons and thy books. Apt were thou to contend for thy "true-bleu" Presbyterianism, with the"jet-black" Prelacy, as thou quaintly calledst it. What wouldst thou do in these more tranquil days? Where find antagonists worthy thy doughty spear? We thank thee for our hold upon this soil where now we worship, none daring to make us afraid; far more do we thank thee for the bold uncompromising frankness to which thou didst incite and train the men whom God gave to thee as a charge for thy keeping, for out of their solid strength the sinews of our freedom came, And thou, John Kirkpatrick, physician, author, and divine, not long we had thee as our own; but when we remember thee, we will not forget the old remembrances of brotherhood, brotherhood in the privations of dissenting citizens and in the triumphs of broadening toleration, brotherhood in the excommunications of Synods and in the joy of new fellowships, wherewith we and our neighbours of another House, though twain, were one. How shall I speak of thee, faithful vindicator of our ancient liberties, Samuel I-Ialiday, dauntless and dignified, who first didst teach us to use the Nonsubscribing name? With thee our direct perceptions of the pure Gospel simplicity, derived from Scripture immediately and alone, first began to tremble into life. Then began men to call us heretics, Arians, infidels, "They say," so runs the famous inscription on the wall of the Marischal College in Aberdeen, "They say -- What say they ? -- Let them say." But thou didst trust, with one of fearless speech and boundless charity, that even as they are of Christ, so also we.

Thy jolly visage on our Vestry wall tells us more of thee than all thy sermons and thy books. Apt were thou to contend for thy "true-bleu" Presbyterianism, with the"jet-black" Prelacy, as thou quaintly calledst it. What wouldst thou do in these more tranquil days? Where find antagonists worthy thy doughty spear? We thank thee for our hold upon this soil where now we worship, none daring to make us afraid; far more do we thank thee for the bold uncompromising frankness to which thou didst incite and train the men whom God gave to thee as a charge for thy keeping, for out of their solid strength the sinews of our freedom came, And thou, John Kirkpatrick, physician, author, and divine, not long we had thee as our own; but when we remember thee, we will not forget the old remembrances of brotherhood, brotherhood in the privations of dissenting citizens and in the triumphs of broadening toleration, brotherhood in the excommunications of Synods and in the joy of new fellowships, wherewith we and our neighbours of another House, though twain, were one. How shall I speak of thee, faithful vindicator of our ancient liberties, Samuel I-Ialiday, dauntless and dignified, who first didst teach us to use the Nonsubscribing name? With thee our direct perceptions of the pure Gospel simplicity, derived from Scripture immediately and alone, first began to tremble into life. Then began men to call us heretics, Arians, infidels, "They say," so runs the famous inscription on the wall of the Marischal College in Aberdeen, "They say -- What say they ? -- Let them say." But thou didst trust, with one of fearless speech and boundless charity, that even as they are of Christ, so also we.

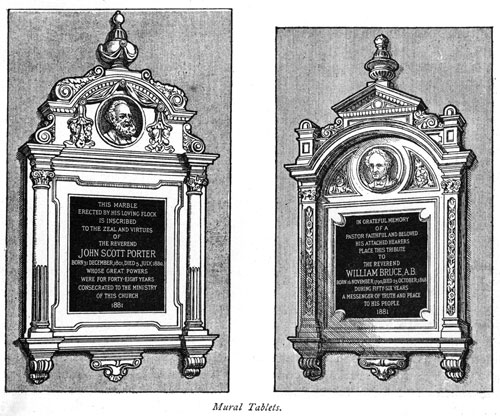

With rapid step we pass along this gallery of spiritual portraits. The gentle and pathetic scholar from whom the poet-patriots of the Drennan line descend; Mackay, the uncle and foster-father of Elizabeth Hamilton; Crombie, of whom in vain we seek some monument, either in the Church which he built, or in the town to which he gave the Academy; the descendant of Scottish King, and, prouder distinction yet, heir of a line unbroken since the Reformation, of Gospel ministers of the King of kings, William Bruce, teacher, theologian, pastor, public man, who first proclaimed, with no uncertain sound, the Unitarian conclusions to which our theology had long been tending. Further we need not go. The marble slabs on either side our pulpit speak the love of this congregation for the imperishable memory of two scholars, thinkers, divines, whose various gifts and special qualities, contrasted in themselves, were united in the edification of the Church they served.

From the time when the Regium Donum began to play a regular part in the State provision for the religious wants of Ireland, Presbyterianism was in a sort of way, and to a minor and strictly subordinate extent, an established form of worship and discipline in this country. Of this quasi-establishment, such as it was, and whatever its advantages and disadvantages, our congregation partook, untill the whole system of State aid to religion in Ireland was dissolved ill 1869. Henceforth we depend mainly upon our own efforts. We have few endowments: the site of our old manse; a property in Waring Street, of which a share was left to us by the late William Tennent in 1832; the proceeds of the commutation of the Regium Donum; these are the chief of our extraneous resources. Our strength must always lie more in the men and women whom we can interest, secure, and educate, in our principles, than in any outward props to our cause. Our wise and thoughtful laity are the real house and stability of our movement. That movement was not hasty in its origin, its spirit has not been flighty in its direction. Firm, steady, persistent, hopeful has been its course. God has gone before it; will He not be its rearword?

DATES. -- Succession of our regular ministry begins, 1660. Regium Donum first granted, 1690; enlarged, 1784, 1792, 1803. Removal to Rosemary Lane, about 1695. Second Congregation founded, 1708. Third Congregation founded, 1722. Our Baptismal Register begins, 1757. Our oldest title and trust deed, 31st August, 1767. Congregational Minute-book begins, 1760. Meeting-house rebuilt, 1783. Skipper Street property, 1833. Dissenters' Chapels Act, 1844. Meeting-House registered for MArriages, 1845. Fee-simple of Meeting-House, &c., acquired, 1855. Northern Presbytery of Antrim, 1862. Disestablishment Act, 1869; came into effect, 1871.