CHAPTER IV

WHAT OUR RELIGIOUS LIFE HAS BEEN AND OUGHT TO BE. A Christian Church. Variations in our public services -- prayer -- praise -- preaching. Religion in common life. Spiritual culture of young and old. Mission work. Propogandism. Our relation to other religious bodies. Personal religion.

![]()

THE Centennial which has called forth the preparation of this volume is not the centennial of our origination as the First Presbyterian Church in Belfast; for this dates back above 240 years. It is not the centennial of our tenure of a religious home in Rosemary Street We have been on this hospitable ground for nearer two centuries than one, and may hold our Rosemary Street bicentennial in 1895, if God spares us. It is not the centennial of our Nonsubscription; brave Halliday won the battle of our Christian liberty 165 years back. It is not the centennial or our Arianism, or of our Unitarianism, for, as we said in our first chapter, the doctrine of the Trinity has never been preached among us since Drennan lifted up his gentle voice in 1736. What, then, did we commemorate in 1883? The re-erection of a building, and therewith the revival, the re-organisation, and practically the re-establishment of our congregational cause.

We were in such low water in 1781, that the dilapidated structure was looked upon as a fit emblem of a falling interest, and if timorous counsels had been attended to, we might have commemorated in 1883, not the new birth of a Meeting-house, but its destruction; not the rejuvenescence of a religious society, but its evaporation or aborption. The courage of our forefathers, under their calm and intelligent leader, James Crombie, was rewarded by the rise of this beautiful House of Prayer, and by the beginning of a new period of religious prosperity for the Church which reassembled within its walls. Fresh heart, quickened energy, an invigorated life had been gained in the experiences of the common work, into which all had thrown themselves with cordial zeal and activity, during the two years of rebuilding.

We were in such low water in 1781, that the dilapidated structure was looked upon as a fit emblem of a falling interest, and if timorous counsels had been attended to, we might have commemorated in 1883, not the new birth of a Meeting-house, but its destruction; not the rejuvenescence of a religious society, but its evaporation or aborption. The courage of our forefathers, under their calm and intelligent leader, James Crombie, was rewarded by the rise of this beautiful House of Prayer, and by the beginning of a new period of religious prosperity for the Church which reassembled within its walls. Fresh heart, quickened energy, an invigorated life had been gained in the experiences of the common work, into which all had thrown themselves with cordial zeal and activity, during the two years of rebuilding.

When the welcome clay arrived, and the Church took possession of its finished sanctuary, it was with increased adherents and brightened hopes. Friends and neighbours in all ranks and denominations had given their sympathy and their encouragement. The lord of the soil, a prelate of the Establishment, the gentry round, the citizens within Belfast, old friends in distant quarters, all had recognised the honourable position, the ancient services, the prospects of further usefulness, the gathered warmth of commendable enterprise, which belonged to the mother church of Presbyterianism, freedom, philanthropy, in Belfast. A spirit ripe and ready for the times animated the congregation, and flinging wide its reconstructed doors with songs of gratitude and praise, it opened on Sunday, 1st June, 1783, a new era of its vitality and its fame.

More than once since that memorable day there has come a period of depression, of anxiety, of searching of heart, in view of the affairs and the apparent prospects of this congregation. More than once have the thoughts of the elders been grave, in the presence of a spirit or listlessness or of timidity. It has never been proposed to pull down this building and do away with it; but there was a passing suggestion, many years ago, to Curtail its proportions. Since then it has been necessary, more than once, to amplify its accommodation. Once for all we may learn, as we look reverently back upon what our fathers feared and what they did a hundred years ago, that the right remedy, in every time of apprehension and drawback and inclination to feel uneasy, is to be found in new engagements, fresh enterprise, a bold seizure or opportunity by hearty co-operation with united mind and will. It is not a history only that we recall, as we go back to the memories of 1781-3; it is a promise we touch, a prophecy that speaks to us. Both God and man help those who have faith and spirit to help themselves.

Hence the value and preciousness of the occasion commemorated by our Centennial lay emphatically in this. It was far more than the successful revival in our general church life. It is an interesting fact that the first publication by Dr. James Crombie, our second founder, as he may be called, was an Essay on Church Consecration (1777), in which he vigorously repudiates the idea of any spiritual virtue or hallowing grace, as residing in any fabric which the hand of man's diligence may raise, or the breath of man's words may set apart. The sanctity of a Christian church, he tells us, is not to be discovered in its habitation, but in its members; consisting, as it does, in "just sentiments of God, impressed upon the soul," in the temper of the worshipping mind, and in the righteous practice which "makes us happy here, and constitutes our bliss hereafter."

Hence the value and preciousness of the occasion commemorated by our Centennial lay emphatically in this. It was far more than the successful revival in our general church life. It is an interesting fact that the first publication by Dr. James Crombie, our second founder, as he may be called, was an Essay on Church Consecration (1777), in which he vigorously repudiates the idea of any spiritual virtue or hallowing grace, as residing in any fabric which the hand of man's diligence may raise, or the breath of man's words may set apart. The sanctity of a Christian church, he tells us, is not to be discovered in its habitation, but in its members; consisting, as it does, in "just sentiments of God, impressed upon the soul," in the temper of the worshipping mind, and in the righteous practice which "makes us happy here, and constitutes our bliss hereafter."

The requisites of a Christian church are three; a Creed, a Worship, an organised and beneficent life.

A Creed we have. But so much has the word been abused, that it is indispensible to explain that when we say Sic credo, "Thus I believe," we do not immediately proceed to crush a personal conviction into an instrument of exclusive privilege. We do not say Sic credendum est, 'So you must believe, or you are outside the pale of the church and of salvation,' Our creed is the flower of our history, that history which has been already sketched in its salient features. We are Unitarians, believing in the Unipersonality of God and in the universal benevolence of the Divine Character, believing in the manifestation of the Eternal Father, through the Perfect Son, whose manhood came from heaven to make God's goodness known. We are Unitarians in our conclusions, yet we do not thereby cease to be Nonsubscribers. We are Unitarians on conviction; Unitarians who rejoice to spread those principles which we have formed. proved, and found to be the strength and blessing of our lives. We are not Unitarians on compulsion, nor would we wear again, or impose on any, the kind of servile yoke from which our fathers were happily delivered. No Unitarian formulary have we signed. Our creed is in our hearts, engraven on our minds. It is inseparable from ourselves. Intelligently we hold it; gladly we proclaim it. We do not enact it into an iron rule by which the faith or the fellowship of future ages is to be restricted and determined.

A Worship we have; and in this most sacred attitude of our minds, this most spiritual purpose of our public association together, we rejoice to know that we are in entire harmony, both of thought and word, with our predecessors, notwithstanding the various phases of theological opinion through which our congregation has passed. Amid all these changes, our worship has uniformly been characterised by its direct address to the Father of all. To forget this, would be to miss the explanation of what puzzles and perplexes those who wonder at us from the outside. How have you kept together, they ask, amazed, during these intellectual revolutions, which have led you from Calvinism to Arminianism, from Arminianism to Unitarianism? What has been your bond, your stay, your common base of religious identity? Why, it has been simply this, that we have always prayed together; offering, with all our differences, a united and continuous worship to Him to whom our Saviour prayed; feeling that though in other matters we might not think alike, in this, the expression of our highest homage, we were truly one, in aspiration, in spirit, in aim. In the matter of religious emotion. no feeling heart will lay down laws in the temper of a martinet. If we have strong feelings towards Christ, we should not hesitate to give them voice, in the invocation of a hymn, or in the frank warmth of a devotional utterance. But that the supreme object of all prayer, all praise, all adoration of the soul, is found in God the Father only, this has been, all along, the one guiding thought of our religion, and this the regulating fact of our sacred and solemn exercIses.

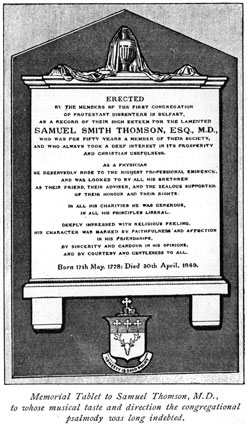

Till the first year of this century, we employed no other hymnal than that sometimes quaint, but often sweet and powerful version of the Psalms, by the Cornish statesman, Sir Francis Rous (1579-1659), which our Scottish ancestors accepted, with some revision (in 1650), as their own; supplemented at a later date by the Scripture Paraphrases (178 I). Thus was our book of praise, throughout our earlier history, completely in unison with the theological convictions of our latest growth, presenting no word or hint of the unscriptural doctrines which we came in course of time to discard. The first edition (1801) of our Psalms and Hymns was a tiny collection of 246 pieces. Since the preparation of the existing edition (1818) containing 300, the stores of modern hymnology have been marvelously enriched in beauty, life, and fulness, and a new book is in progress. But we owe much to the collection which we have so long employed, especially to its marked devotional quality, and would not willingly lose the treasures, dear to many a religious association, which its familiar pages enshrine. The introduction of an organ among us was strongly resisted for a long period; and though the architect who designed our galleries, himself a churchman, intended from the first that the organ gallery should serve its present use, it was seventy years before an instrument was placed there. What was feared by Dr. Bruce, was, that the mechanical aid might prove the destruction of congregational psalmody, a danger, perhaps, not wholly unreal. No litany, and no responsive prayer have we, but in sonorous hymn and simple chant, all may join, and be the better of it. The most impressive song of worship is that in which the chorus of the congregation rises, in honest, not self-conscious notes, with melody, perhaps unskilled, but from the heart. For music more elaborate, the anthem, which forms a part of all our regular services, gives scope. Our present collection of Chants and Anthems, edited under the superintendence of our accomplished organist, Dr. Carroll, dates from 1866.

Till the first year of this century, we employed no other hymnal than that sometimes quaint, but often sweet and powerful version of the Psalms, by the Cornish statesman, Sir Francis Rous (1579-1659), which our Scottish ancestors accepted, with some revision (in 1650), as their own; supplemented at a later date by the Scripture Paraphrases (178 I). Thus was our book of praise, throughout our earlier history, completely in unison with the theological convictions of our latest growth, presenting no word or hint of the unscriptural doctrines which we came in course of time to discard. The first edition (1801) of our Psalms and Hymns was a tiny collection of 246 pieces. Since the preparation of the existing edition (1818) containing 300, the stores of modern hymnology have been marvelously enriched in beauty, life, and fulness, and a new book is in progress. But we owe much to the collection which we have so long employed, especially to its marked devotional quality, and would not willingly lose the treasures, dear to many a religious association, which its familiar pages enshrine. The introduction of an organ among us was strongly resisted for a long period; and though the architect who designed our galleries, himself a churchman, intended from the first that the organ gallery should serve its present use, it was seventy years before an instrument was placed there. What was feared by Dr. Bruce, was, that the mechanical aid might prove the destruction of congregational psalmody, a danger, perhaps, not wholly unreal. No litany, and no responsive prayer have we, but in sonorous hymn and simple chant, all may join, and be the better of it. The most impressive song of worship is that in which the chorus of the congregation rises, in honest, not self-conscious notes, with melody, perhaps unskilled, but from the heart. For music more elaborate, the anthem, which forms a part of all our regular services, gives scope. Our present collection of Chants and Anthems, edited under the superintendence of our accomplished organist, Dr. Carroll, dates from 1866.

Preaching, with us, as with all Presbyterians, has been viewed far more as an integral part of worship than as an extraneous addition to it. Listening to sermons constitutes one or our best recognised religious engagements. Mindful of this, successive preachers here have directed their efforts mainly to practical points of religious edification; not inculcating theological niceties, but endeavouring to reach the conscience, to elevate the moral tone, and to deepen the spiritual life. It has been an interesting task to read and compare, for the purposes of this historical survey, a large number of specimens of the pulpit work of this church, some in print, some in manuscript, from Patrick Adair downwards through all the variations of theological change. Very remarkable is the great similarity of spirit, even when controversy is in question; very marked is the essential harmony of the prevailing tone of the general teaching, which is decidedly not controversial.  The strain has been didactic, rather than emotional; but the main business and substance of the preacher's discourse has not been to give lectures in theology, but lessons of life, aids to the perfecting of the moral ideal, encouragements to the waiting upon the power of God in the soul. When Patrick Adair says, "on a sacrament day," in 1672; "Whatever way people do seek Christ, they do find him, Those that seek no more than Christ's outward presence, he will consent to give them that; but those that seek his spiritual presence, he will hear them also in that," he exhibits a power of generous appreciation of different stages of religious experience, and points, at the same time, to the true line of religious advance. Or when John M'Bride, also at a sacramental season, preaches, as his manner was, four successive sermons on the same text, and that the text which speaks of a good conscience, enforcing this as the test of spiritual health and vigour, we feel that, though the doctrines on which his eye was fixed were different from ours, his point of view was essentially one with our own.

The strain has been didactic, rather than emotional; but the main business and substance of the preacher's discourse has not been to give lectures in theology, but lessons of life, aids to the perfecting of the moral ideal, encouragements to the waiting upon the power of God in the soul. When Patrick Adair says, "on a sacrament day," in 1672; "Whatever way people do seek Christ, they do find him, Those that seek no more than Christ's outward presence, he will consent to give them that; but those that seek his spiritual presence, he will hear them also in that," he exhibits a power of generous appreciation of different stages of religious experience, and points, at the same time, to the true line of religious advance. Or when John M'Bride, also at a sacramental season, preaches, as his manner was, four successive sermons on the same text, and that the text which speaks of a good conscience, enforcing this as the test of spiritual health and vigour, we feel that, though the doctrines on which his eye was fixed were different from ours, his point of view was essentially one with our own.

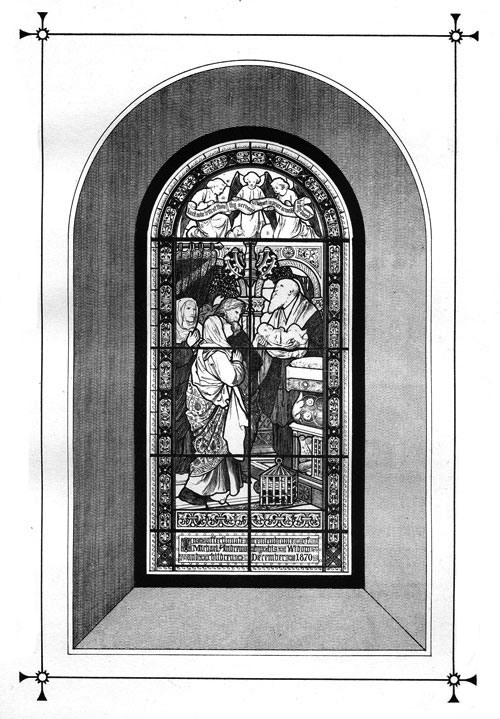

If resort to preaching be the most prominent and comprehensive of our religious observances, attendance on communions is the most significant. Our ancestors regarded this rite with an awe and reverence approaching the confines of superstitious dread. Hence the infrequency of their celebrations (originally but once a-year in each congregation), the sedulous and searching care of their preparations, and their public thanksgiving days after participation. Early in the last century, the communion was celebrated among us in February and August, but the change to April and October preceded the erection of our present Meeting-house. Our conservative ways are still apparent in our traditional use of unleavened bread, though we have discarded the qualifying tokens, and have recently abandoned the ancient custom of sitting around the Lord's table in successive relays. But the communion is still to us the binding ordinance of our public religion. The symbol and the pledge of our Christian fellowship and profession has a hold upon our affection, stronger than that of our ordinary worship. A minister accustomed to English usages, who was present at one of our recent communions, declared it to be a wonder and a joy to him, to see a whole congregation of Unitarians staying to participate in this beautiful and solemnising rite, which is at once the crown of our devotion to the Giver of all spiritual food, and the seal of our adherence to the cause of Christ.

If resort to preaching be the most prominent and comprehensive of our religious observances, attendance on communions is the most significant. Our ancestors regarded this rite with an awe and reverence approaching the confines of superstitious dread. Hence the infrequency of their celebrations (originally but once a-year in each congregation), the sedulous and searching care of their preparations, and their public thanksgiving days after participation. Early in the last century, the communion was celebrated among us in February and August, but the change to April and October preceded the erection of our present Meeting-house. Our conservative ways are still apparent in our traditional use of unleavened bread, though we have discarded the qualifying tokens, and have recently abandoned the ancient custom of sitting around the Lord's table in successive relays. But the communion is still to us the binding ordinance of our public religion. The symbol and the pledge of our Christian fellowship and profession has a hold upon our affection, stronger than that of our ordinary worship. A minister accustomed to English usages, who was present at one of our recent communions, declared it to be a wonder and a joy to him, to see a whole congregation of Unitarians staying to participate in this beautiful and solemnising rite, which is at once the crown of our devotion to the Giver of all spiritual food, and the seal of our adherence to the cause of Christ.

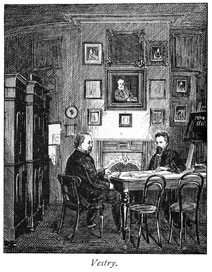

An organised Church Life we have. Inheritors of the free traditions of a popular Presbyterianism, we have found its machinery elastic enough to provide for the expansion of our ideas, and the altering conditions of our various work. In 1760, was added to a Iifelong eldership, a congregational committee, forming a sessional body, periodically renewed.

An organised Church Life we have. Inheritors of the free traditions of a popular Presbyterianism, we have found its machinery elastic enough to provide for the expansion of our ideas, and the altering conditions of our various work. In 1760, was added to a Iifelong eldership, a congregational committee, forming a sessional body, periodically renewed.

The Presbyterian system may legitimately be regarded as that of which the outline is foreshadowed in the New Testament. But it would neither be just nor wise to stickle for it as constituting a part of the substance of revelation. Forms of church government are matters of constitutional expedience, rather than of divine right, in an exclusive sense. Presbyterianism, fairly administered, has proved itself a most valuable and sufficient instrument for training the mind, disciplining the energies, eliciting and giving effect to the real convictions of a religious body. Besides this, it has rendered important services in directing the aid of strong congregations to the conservation of weak ones, both by moral support, and by material aid. No system, however, can do more for congregations than they are willing to do for themselves. Nor can any reliance upon religious ordinances supply the lack of the personal life of religion; nor any creed suffice to make men good.

Great store is set, by people of our creed, upon the religion of common life, and rightly so. A good home religion, a good Monday religion, a good business and market religion, a religion of week-day duties and veracities and generosities and charities, a religion that follows men behind the counter, and is not left in the pew, a religion that is not stifled in the hour of pleasure, to be roused again in the hour of prayer, a religion that keeps the heart clean, and the conduct straight; this is the religion which commands our suffrages, holds our esteem, and animates our ideal of the life that best serves God. But it would be a fatal mistake to suppose this religion, the religion of life and conduct, the practical religion of character, attainable in any high degree, without spiritual culture. You cannot regulate the actions of the outward man, without educating the motives of the inward man. As our Saviour says, "Make the tree good," if you want the fruit to be wholesome and sound.

Great store is set, by people of our creed, upon the religion of common life, and rightly so. A good home religion, a good Monday religion, a good business and market religion, a religion of week-day duties and veracities and generosities and charities, a religion that follows men behind the counter, and is not left in the pew, a religion that is not stifled in the hour of pleasure, to be roused again in the hour of prayer, a religion that keeps the heart clean, and the conduct straight; this is the religion which commands our suffrages, holds our esteem, and animates our ideal of the life that best serves God. But it would be a fatal mistake to suppose this religion, the religion of life and conduct, the practical religion of character, attainable in any high degree, without spiritual culture. You cannot regulate the actions of the outward man, without educating the motives of the inward man. As our Saviour says, "Make the tree good," if you want the fruit to be wholesome and sound.

This work of spiritual culture is our great business with the young. This is the object of our Sunday Schools, our classes, our children's services. We have to train young minds in our ideas, not simply because they are ours, but because we believe them to be the best. We have to awaken in young hearts a glad response to the verities of our pure and holy faith, that their lives may be biassed in the right direction from the first. We have to encourage them to think for themselves, and spur them to act for themselves; but we are bound to give them, at the beginning, the best materials for thinking, and best guidance for action. If we neglect this, we neglect their future, we surrender the prospects of our cause, we destroy our best hope. Not one of us would wish to see our young people converted into Unitarian bigots; but we do all of us desire to see them grow up intelligent Unitarians, knowing something of the historic past from which we spring, and understanding how to value it and to apply its lessons, having our principles at heart and ready to stand by them, permeated with our faith in God, actuated by what we have learned of Christ, at home in the sacred Scriptures, and prizing them with an appreciative and grateful love. This we do earnestly desire, and this we must all aim at, and determine to bring about. This if we cannot do, we can do nothing. A hundred years have passed since our forefathers, with Christian manliness, resolved not to accept a verdict of unsuccess, but reared our Meeting-house, in confident and courageous faith. We have learned to speak out our thoughts more boldly since then, to call things by their right names, to define our position, to own and to defend our theology. What were all this, if we cared not to provide for our own household? Better, according to the Apostle, to deny the faith at once; the worst species of infidelity to our sacred cause is to believe that it is not worth while to secure its influence over the rising life or our own immediate flock. Nothing which we have devised to celebrate this Centennial of ours, gives promise of so much permanent advantage as this, that we have seized the golden opportunity of making new provision for the housing of our Sunday School, our Libraries, our gatherings for religious and intellectual improvement, under the auspices of such fraternities as our Institute of Faith and Science.

That we have a mission to the world outside is most true. But practical men to whom we may address ourselves, will measure our movement by measuring us; will estimate it not by the abstract beauty of our tenets, but by the degree and quality of the results which they perceive to be registered in our individual characters, and in our church life. A prosperous, animated, energetic, and united church is always a missionary church. It always exercises a demonstrable influence on behalf of the principles it espouses. It earns the right to some attention; it conciliates respect; it creates a presumption in its own favour, People say 'There is power in it; there is an example about it; we must look at it; we may learn from it.'

Upon this church of ours, two classes of eyes are steadily fixed. Turning towards us in warm sympathy and cordial hope, the sister churches of our communion throughout the North of Ireland await our movements, and scan our course. Naturally they expect it of us to set a tone, to keep a lead in good works, to encourage others, to present, not merely a fair Meeting-house, as our inheritance from the past, but an earnest, living church, thoroughly abreast of the times, as our pledge of the future.

Upon this church of ours, two classes of eyes are steadily fixed. Turning towards us in warm sympathy and cordial hope, the sister churches of our communion throughout the North of Ireland await our movements, and scan our course. Naturally they expect it of us to set a tone, to keep a lead in good works, to encourage others, to present, not merely a fair Meeting-house, as our inheritance from the past, but an earnest, living church, thoroughly abreast of the times, as our pledge of the future.

Again, we are exposed to a tolerably shrewd and searching scrutiny, cast upon our doings and not-doings, by the great mass of religionists who refuse to admit us within the pale of their brotherhood. Criticism from the outside, however unsympathetic, never does much harm to a resolute cause. It acts as a tonic; bitter, but bracing. We have long been made conscious that whatever we do for our religion, we must do in a sort of ostracised isolation. None but weak minds will waste time in complaining of this. We must accept it as a part of the conditions of the situation, a factor in our particular problem, and determine not to be rendered idle by lack of hearty cooperation and friendly fellowship, in quarters where our principles are painted black. We must show what these dreadful Unitarians are capable of.

And further, we must take into account that there is very much latent aud covert sympathy, both with our persons, as men of honour and principle, as citizens who have won respect, and with our views, as giving decided expression to tendencies powerfully felt in all denominations. There are those who are looking at us, not inimically, but wistfully, acknowledging our constancy, envying our freedom, in much accord with many or most of our conclusions, finding in us much to admire; conscious that they would gain in consistency, thoroughness, mental purity, if they came over to our position, yet wondering whether, on the whole, they would not lose something which is spiritually precious to them, by a clear identification with us; and finally kept aloof from us, because they are told (and find some colour for the calumny) that we are cold in our own despite, indifferent to our own interests; our principles firm, our energies slow; our wealth rarely applicable to our own objects; great opportunities before us, the pulse of our zeal somewhat slack to embrace them. We shall not admit the justice of this feeling, but we must all have observed its existence. Everyone of us must do what in us lies to remove it, not for our own sakes only, but for the sake also of those to whom it will prove the greatest of religious blessings to learn that Unitarianism can be compatible with ardour, enterprise, endeavour, the mainspring, the influential creative force of a strong and flourishing cause.

And further, we must take into account that there is very much latent aud covert sympathy, both with our persons, as men of honour and principle, as citizens who have won respect, and with our views, as giving decided expression to tendencies powerfully felt in all denominations. There are those who are looking at us, not inimically, but wistfully, acknowledging our constancy, envying our freedom, in much accord with many or most of our conclusions, finding in us much to admire; conscious that they would gain in consistency, thoroughness, mental purity, if they came over to our position, yet wondering whether, on the whole, they would not lose something which is spiritually precious to them, by a clear identification with us; and finally kept aloof from us, because they are told (and find some colour for the calumny) that we are cold in our own despite, indifferent to our own interests; our principles firm, our energies slow; our wealth rarely applicable to our own objects; great opportunities before us, the pulse of our zeal somewhat slack to embrace them. We shall not admit the justice of this feeling, but we must all have observed its existence. Everyone of us must do what in us lies to remove it, not for our own sakes only, but for the sake also of those to whom it will prove the greatest of religious blessings to learn that Unitarianism can be compatible with ardour, enterprise, endeavour, the mainspring, the influential creative force of a strong and flourishing cause.

The mission beyond our own borders, in which we take the keenest interest, and to which we render our most active aid, is a service of Christian benevolence, a work not of propagandism, but of moral elevation and wise charity. Here we feel deeply in earnest, and here, accordingly, we succeed. This mission has taken many forms in our past history. The Domestic Mission (1853) which we largely support, and which owes its inception to the awakening word of one of our excellent ladies, is but one phase of the various schemes and unselfish agencies, from time to time originated and sustained by the members of our communion, in fulfillment of a recognised duty towards souls and bodies languishing around us.

Scarcely, as yet, is our conscience profoundly stirred by the obligation "to do good and to communicate," as respects our positive tenets and principles as a denomination. Hence the personal energy which we throw into this work is very slight, and does not at all represent the value we really set upon our express doctrinal beliefs. Lukewarm we are not, as is proved when we are roused to the defence of what we hold dear, by the assaults of the supposed "orthodox," or the attempts of those who do not understand that we cherish a distinctive Christian creed, and have no notion of surrendering it. But at ordinary times, and when not specially put upon our mettle, we are very placid in our contentment with the possession of the truth, and exceedingly calm in our contemplation of the world's neglect of it. Offering in a quiet way the stores of our literature to the passer by, we say, in effect, 'Take it, or leave it.' There is something of mental dignity in this self-contained and uneager attitude. But is it really all we are capable of ? -- all that we find in our heart of hearts? Are we quite satisfied with it? Is it not fair to interpret the needs of our time by urging the imperative and present claims of a Unitarian enthusiasm, a Unitarian activity, yes, of a Unitarian propagandism? Let none start at the term. It is a wise husbandman's word. We must plant out bravely and boldly to-day, if we are to have a growth that is to flower and thrive in future years.

Our relation to other religious bodies is, as has been already said, one of isolation; a feeling of suspicion on their part, a sense of ostracism on ours. Old memories tell us it was not always so. But let us look back a little, beyond the memory of the oldest. In the early days of the settlement or our cause, things were far more severe and trying in this respect than they are now. Think of the times when Church and State combined against us, times of penal Acts and vindictive prosecutions, when our ancestors and our spiritual harbingers were ejected, exiled, incarcerated. Some of the dread experiences of those times have been recounted in the preceding chapters. Our forerunners endured the worst that men could do to shake and bend them. Men saw that they meant to live, and learned to respect them accordingly. A Bishop drove us from the "publique meeting place," and compelled us to seek and make a habitation of our own. Another Bishop, after 120 years of our independent persistency, sent his donation to the building of the house in which we meet. A clergyman (William Bristow) fulminated against us for what he was pleased to term our "schism," though, as colonists from Scotland, we had never owned or owed allegiance to the Episcopal Establishment; later on, that same clergyman, in spite of Crombie's bold reply, came hither on a Sunday evening, and held the collecting plate, after a sermon for one of our charities. That was in the halcyon days, when religious animosities slept, and good men of all creeds felt the harmony of their work, in presence of common dangers. Then came the terrible outspokenness of this Unitarianism. Neighbours fell back; members deserted us; the timid and careless sought a shelter from odium in the safe places of the Establishment. Some, doubtless, were drawn from us by an awakened conviction that we were wrong. For there had been much indifference in those happy days; other things slept besides religious animosity; and the Unitarian avowal forced men to have real opinions on one side or the other.

Our relation to other religious bodies is, as has been already said, one of isolation; a feeling of suspicion on their part, a sense of ostracism on ours. Old memories tell us it was not always so. But let us look back a little, beyond the memory of the oldest. In the early days of the settlement or our cause, things were far more severe and trying in this respect than they are now. Think of the times when Church and State combined against us, times of penal Acts and vindictive prosecutions, when our ancestors and our spiritual harbingers were ejected, exiled, incarcerated. Some of the dread experiences of those times have been recounted in the preceding chapters. Our forerunners endured the worst that men could do to shake and bend them. Men saw that they meant to live, and learned to respect them accordingly. A Bishop drove us from the "publique meeting place," and compelled us to seek and make a habitation of our own. Another Bishop, after 120 years of our independent persistency, sent his donation to the building of the house in which we meet. A clergyman (William Bristow) fulminated against us for what he was pleased to term our "schism," though, as colonists from Scotland, we had never owned or owed allegiance to the Episcopal Establishment; later on, that same clergyman, in spite of Crombie's bold reply, came hither on a Sunday evening, and held the collecting plate, after a sermon for one of our charities. That was in the halcyon days, when religious animosities slept, and good men of all creeds felt the harmony of their work, in presence of common dangers. Then came the terrible outspokenness of this Unitarianism. Neighbours fell back; members deserted us; the timid and careless sought a shelter from odium in the safe places of the Establishment. Some, doubtless, were drawn from us by an awakened conviction that we were wrong. For there had been much indifference in those happy days; other things slept besides religious animosity; and the Unitarian avowal forced men to have real opinions on one side or the other.

What was the meaning of this outspokenness which severed so many ties. It meant that we could no longer keep to ourselves, or restrain the inward pressure of imperative truth. We knew that to be serious, frank, and genuine, was, better than being pelted. Our avowed Unitarianism has not yet held its own for the period which intervened between the Bishop who persecuted, and the Bishop who patronised us. Yet, even now, people are beginning to appreciate, better than they once did, the true significance of our position, to recognise that we take our stand, not for a whim of being singular, nor because we have no religion, but because we set the Christ of God above the creeds of men, and conscience above conformity. Keep true to your own principles; let men see that they make you earnest, united, thorough, energetic, benevolent; and they will hold out the hand by-and-by.

What was the meaning of this outspokenness which severed so many ties. It meant that we could no longer keep to ourselves, or restrain the inward pressure of imperative truth. We knew that to be serious, frank, and genuine, was, better than being pelted. Our avowed Unitarianism has not yet held its own for the period which intervened between the Bishop who persecuted, and the Bishop who patronised us. Yet, even now, people are beginning to appreciate, better than they once did, the true significance of our position, to recognise that we take our stand, not for a whim of being singular, nor because we have no religion, but because we set the Christ of God above the creeds of men, and conscience above conformity. Keep true to your own principles; let men see that they make you earnest, united, thorough, energetic, benevolent; and they will hold out the hand by-and-by.

The root of all success lies in personal qualities, and in their persistent application to some definite end. Our end and aim, as a congregation, is to spread the Kingdom of God, to diffuse the spirit of Christ, to deepen the power of religion. We cannot do this, unless first we have that Kingdom in our hearts, obey that spirit In our lives, feel that power in our own souls. Personal religion is beyond all things else, the one great need. Our ancestors were men of courage, for they were men of faith, men of power inasmuch as they were men of prayer. In deep distresses their hearts were full of joy; the praises of God were on their lips, because the sense of His mercies filled their souls. They followed the simple word of Christ, through difficulty and danger and temptation, through good report and ill, because they knew in whom they believed. There is no other way for us than their way. We have outgrown the measure of their thoughts; but their spirit, their example, their devoutness, their sincerity, the enthusiasm of their allegiance to truth and goodness, their self-surrender to God, in the love of Christ, these are their imperishable bequests. Taught of the Lord through them, we have to transmit the lesson to those that shall come after us, that great may be the peace of our children; that so, in days to come, they who shall worship in our places when we are gathered to our fathers, may forget our mistakes, and take no pattern by our shortcomings, but sometimes remember our aspirations and our hopes, and, cleaving fast to whatsoever things are true, honourable, just, and pure, may still, when we are dust, "offer up spiritual sacrifices, acceptable to God, through Jesus Christ."

DATES. -- Crombie's Essay on Church Consecration, 1777. Our Hymn-book, first edition, 1801; second edition, 1818. Congregational Library founded, 1838. Sunday School begun, 1838. Day School established, 1838. Organ introduced, 1853, new Organ, 1856. Domestic Mission, 1853. Minister's Library, 1868. Mission Fund of Nonsubscribing Association, 1881. Centennial celebration, 1883.